Lecture 3

Logistic Regression

Logistic Regression

Roadmap

Concepts: what logistic regression is and how classification is evaluated

R coding labs: fitting models, average marginal effects, predicting probabilities, tuning thresholds, and reporting results

By the end of this mini-unit, you should be able to:

- explain why logistic regression is used for binary outcomes

- connect probability ↔︎ odds ↔︎ log-odds (logit)

- describe estimation at a high level (likelihood and deviance)

- compare models using AIC and BIC

- convert predicted probabilities into a classifier using a threshold

- evaluate classification using confusion matrix, precision, recall, specificity, and ROC/AUC

- recognize common issues: class imbalance and (quasi-)separation

Motivation: binary outcomes

Many problems are naturally yes/no (0/1):

- Will a flight be delayed?

- Will a customer churn?

- Is a newborn “at-risk”?

We want:

- Relationship: how predictors change the probability of the outcome

- Prediction (Classfication): a model that produces useful predicted probabilities

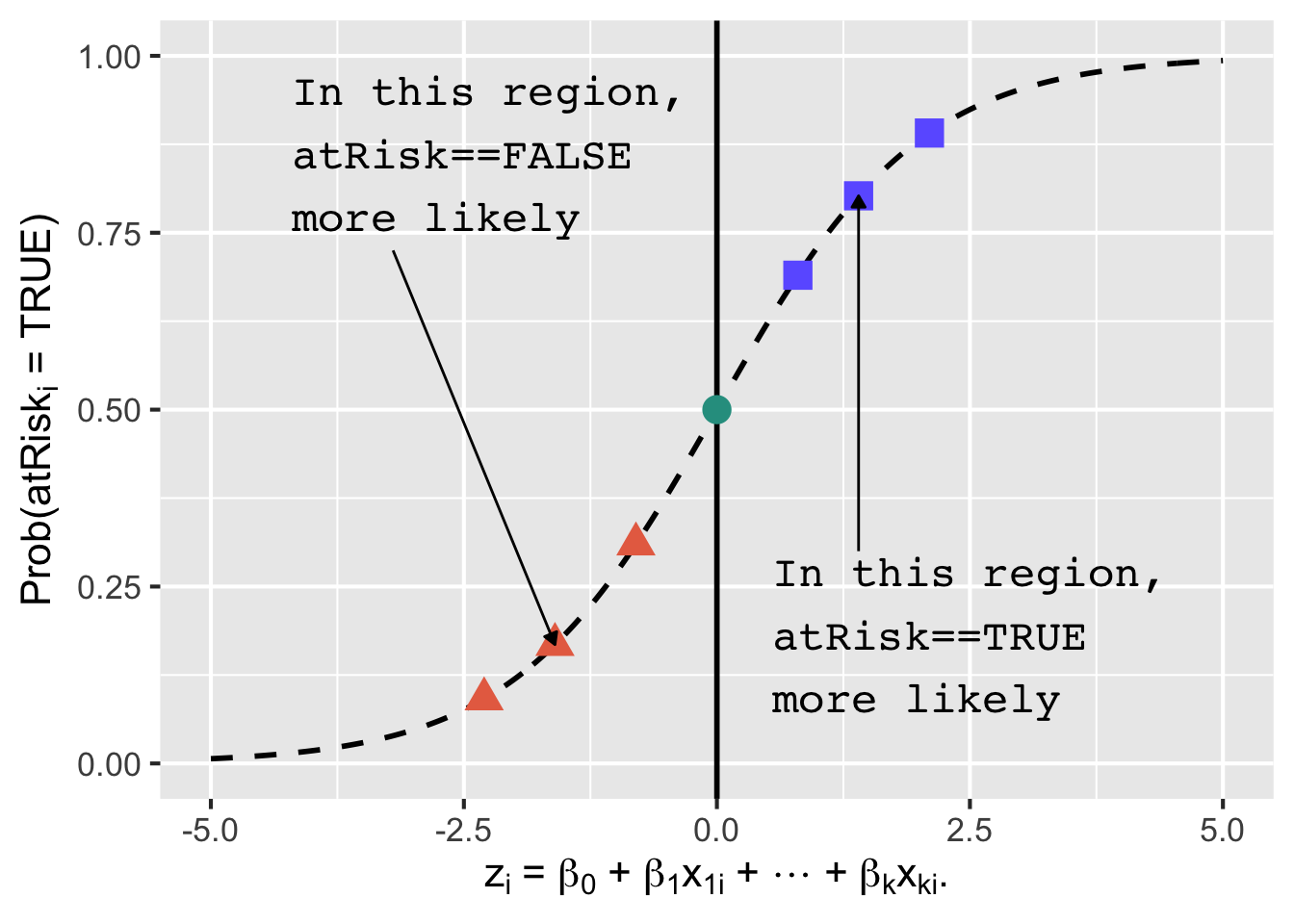

Logistic Regression Model

Let the linear combination of predictors be

\[ z_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1,i} + \cdots + \beta_k x_{k,i}. \]

Logistic regression models the probability

\[ \Pr(y_i = 1 \mid x_i) = G(z_i) = \frac{\exp(z_i)}{1 + \exp(z_i)}. \] That is, the logistic function \(G(z_i)\) maps the linear combination of predictors to the probability that the outcome \(y_{i}\) is \(1\):

\[ z_{i} \rightarrow \Pr(y_i = 1 \mid x_i). \]

Logistic Function

Properties of the Logistic Function

- Range: for any real number \(z\), \(G(z) \in (0,1)\)

- Monotone: larger \(z\) → larger probability

- S-shaped: the “same” change in \(z\) has different impact depending on where you are on the curve

Interpretation:

- \(z_i\) is the model’s score (unbounded)

- \(G(z_i)\) is the predicted probability (bounded)

What is the Logistic Regression doing?

- The logistic regression finds the beta coefficients, \(b_0\), \(b_1\), \(b_2\), \(\cdots\), \(b_{k}\) such that the logistic function \[ G(b_0 + b_{1}x_{1,i} + b_{2}x_{2,i} + \,\cdots\, + b_{k}x_{k,i}) \] is the best possible estimate of the binary outcome \(y_{i}\).

What is the Logistic Regression doing?

The function \(G(z_i)\) is called the logistic function because the function \(G(z_i)\) is the inverse function of a logit (or a log-odd) of the probability that the outcome \(y_{i}\) is 1. \[ \begin{align} G^{-1}(z_i) &\,\equiv\, \text{logit} (\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1))\\ &\,\equiv \log\left(\, \frac{\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1)}{\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 0)} \,\right)\\ &\,=\, b_0 + b_{1}x_{1,i} + b_{2}x_{2,i} + \,\cdots\, + b_{k}x_{k,i} \end{align} \]

Logistic regression is a linear regression model for log odds.

Likelihood

Deviance and Likelihood

- Deviance is a measure of the distance between the data and the estimated model.

\[ \text{Deviance} = -2 \log(\text{Likelihood}) + C, \] where \(C\) is constant that we can ignore.

Deviance and Likelihood

- Logistic regression finds the beta coefficients, \(b_0, b_1, \,\cdots, b_k\) , such that the logistic function

\[ G(b_0 + b_{1}x_{1,i} + b_{2}x_{2,i} + \,\cdots\, + b_{k}x_{k,i}) \]

is the best possible estimate of the binary outcome \(y_i\).

Logistic regression finds the beta parameters that maximize the log likelihood of the data, given the model, which is equivalent to minimizing the sum of the residual deviances.

- When you minimize the deviance, you are fitting the parameters to make the model and data look as close as possible.

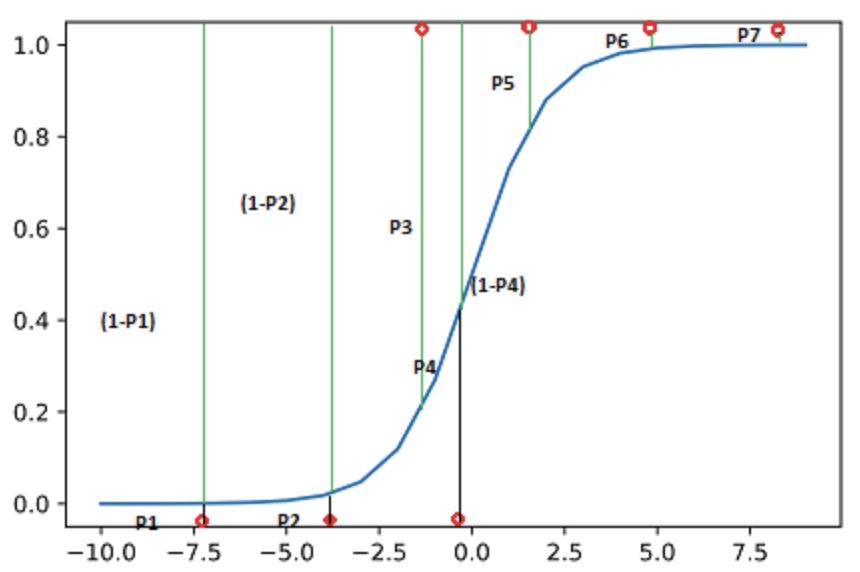

Likelihood Function

- Likelihood is the probability of your data given the model.

- The probability that the seven data points would be observed:

- \(L = (1-P1)\times(1-P2)\times P3 \times (1-P4) \times P5 \times P6 \times P7\)

- The log of the likelihood: \[ \begin{align} \log(L) &= \log(1-P1) + \log(1-P2) + \log(P3) \\ &\quad+ \log(1-P4) + \log(P5) + \log(P6) + \log(P7) \end{align} \]

AIC and BIC (Model Selection Intuition)

\[ \text{AIC} = -2\,\log L + 2k \qquad\qquad \text{BIC} = -2\,\log L + k\log(n) \]

- AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) help you compare candidate models fit to the same outcome on the same dataset.

- They answer a practical question:

“Is the improvement in fit worth the extra complexity?”

- Both start from the badness-of-fit term: \(-2\log(L)\)

- Smaller AIC/BIC means the model explains the data better.

- Then they add a penalty for estimating more parameters (\(k\)):

- More parameters → more flexibility → higher risk of overfitting.

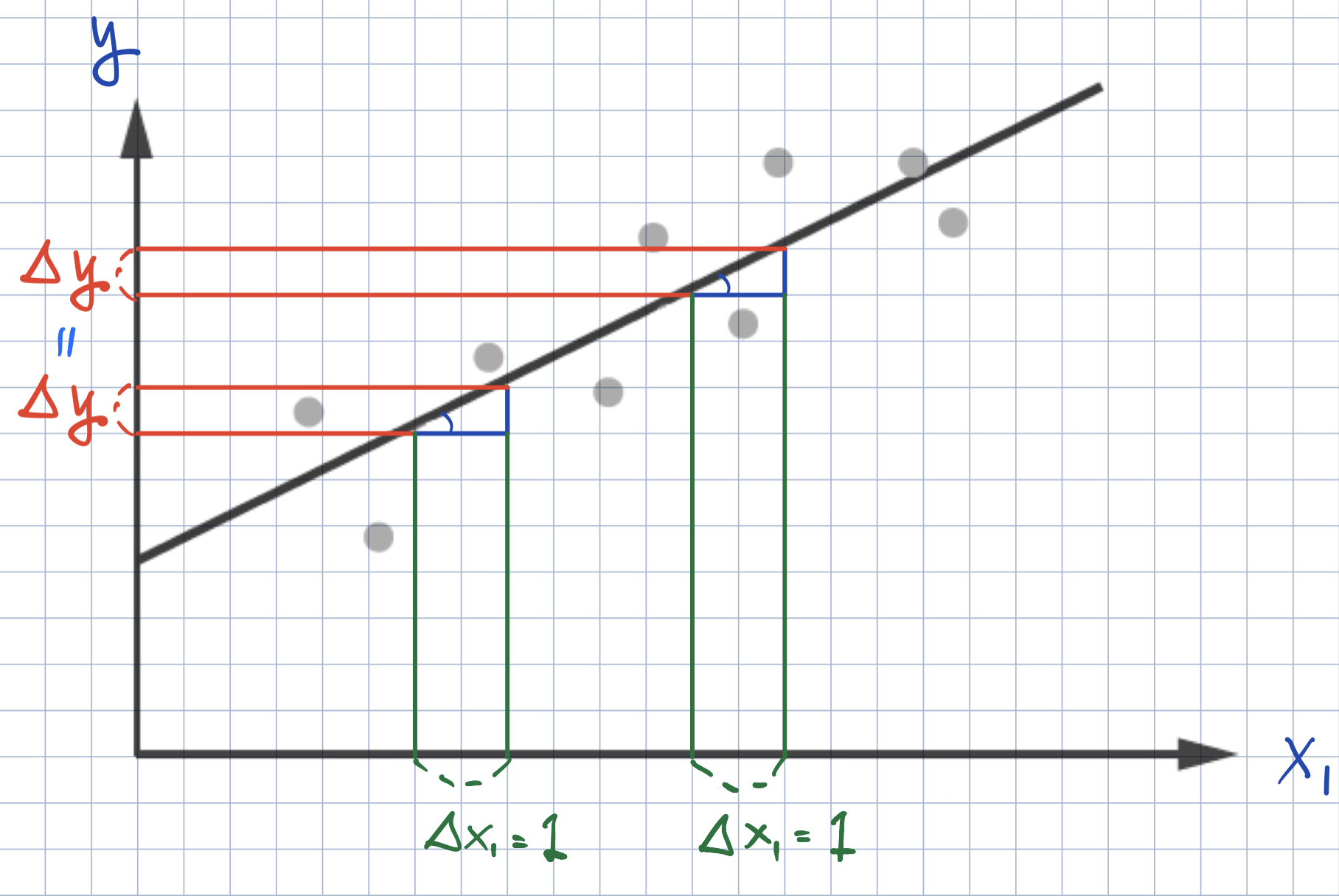

Marginal Effects

Interpreting Beta Coefficients

- Logistic regression can be expressed as linear regression of log odds of \(y_{i} = 1\) on predictors \(x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_k\):

\[ \begin{align} \text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1) &\,=\, G( b_0 + b_{1}x_{1,i} + b_{2}x_{2,i} + \,\cdots\, + b_{k}x_{k,i} )\\ \text{ }\\ \Leftrightarrow\qquad \log\left(\dfrac{\text{Prob}( y_i = 1 )}{\text{Prob}( y_i = 0 )}\right) &\,=\, b_0 + b_{1}x_{1,i} + b_{2}x_{2,i} + \,\cdots\, + b_{k}x_{k,i} \end{align} \]

A one-unit increase in \(x_k\) changes the log-odds by \(\beta_k\).

For a binary predictor, it’s relative to the reference category.

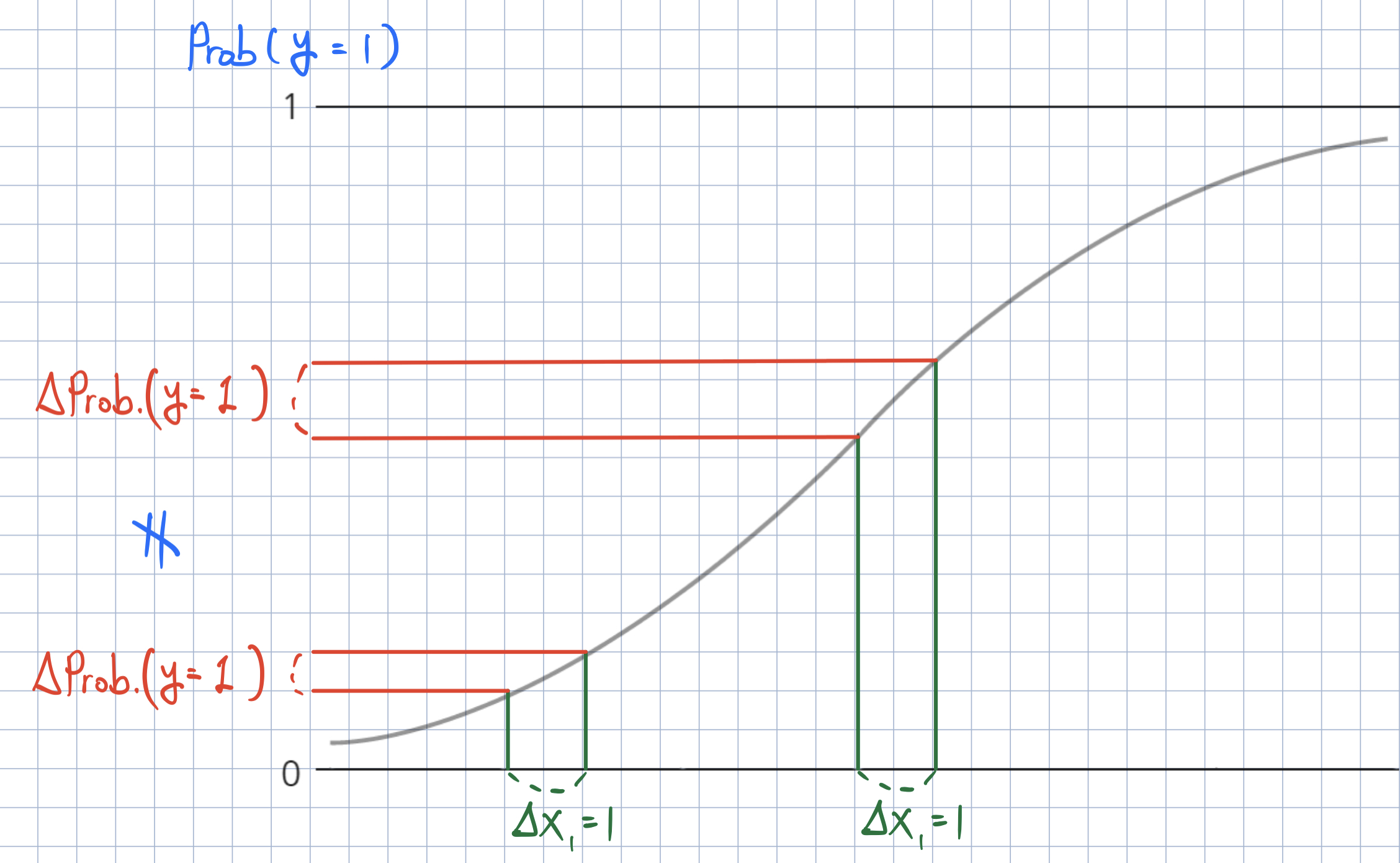

Marginal Effects

In logistic regression, the coefficient \(\beta_k\) is not a constant change in probability but the log-odds.

The marginal effect on the probability depends on \(z_i\):

\[ \frac{\partial p_i}{\partial x_{k,i}} = \beta_k \; p_i (1-p_i). \]

So the same \(\beta_k\) can imply different probability changes for different observations.

Marginal Effect of \(x_{k, i}\) on \(\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1)\)

- In logistic regression, the effect of \(x_{k, i}\) on \(\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1)\) is different for each observation \(i\).

Marginal Effect of \(x_{k, i}\) on \(\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1)\)

- How can we calculate the effect of \(x_{k, i}\) on the probability of \(y_{i} = 1\)?

- MEM (marginal effect at the mean): compute ME at a “typical” case

- AME (average marginal effect): average the ME across observations

- MEM (marginal effect at the mean): compute ME at a “typical” case

% vs. % point

- Let’s say you have money in a savings account. The interest is 3%.

- Now consider two scenarios:

- The bank increases the interest rate by one percent.

- The bank increases the interest rate by one percentage point.

- What is the new interest rate in each scenario? Which is better?

Classification

Classifier

- Your goal is to use the logistic regression model to classify newborn babies into one of two categories—at-risk or not.

- Prediction from the logistic regression with a threshold on the predicted probabilities can be used as a classifier.

- If the predicted probability that the baby \(\texttt{i}\) is at risk is greater than the threshold, the baby \(\texttt{i}\) is classified as at-risk.

- Otherwise, the baby \(\texttt{i}\) is classified as not-at-risk.

- Double density plot is useful when picking the classifier threshold.

- Since the classifier is built using the training data, the threshold should also be selected using the training data.

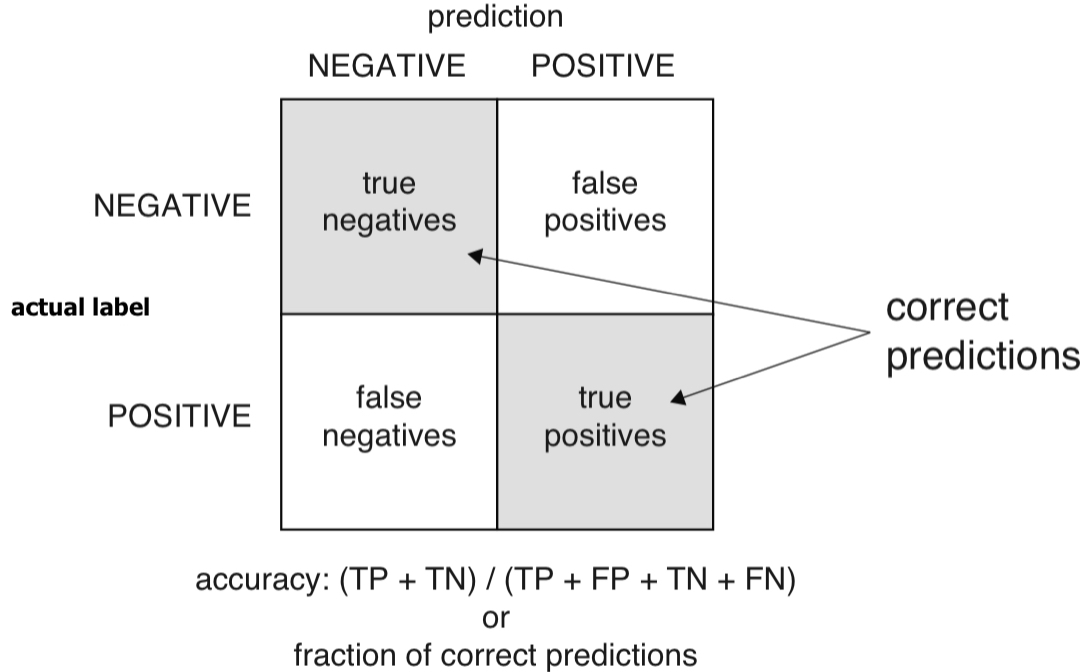

Accuracy

- Accuracy: When the classifier says this newborn baby is at risk or is not at risk, what is the probability that the model is correct?

- Accuracy is defined as the number of items categorized correctly divided by the total number of items.

False positive/negative

- False positive rate (FPR): If the classifier says this newborn baby is at risk, what’s the probability that the baby is not really at risk?

- FPR is defined as the ratio of false positives to predicted positives.

- False negative rate (FNR): If the classifier says this newborn baby is not at risk, what’s the probability that the baby is really at risk?

- FNR is defined as the ratio of false negatives to predicted negatives.

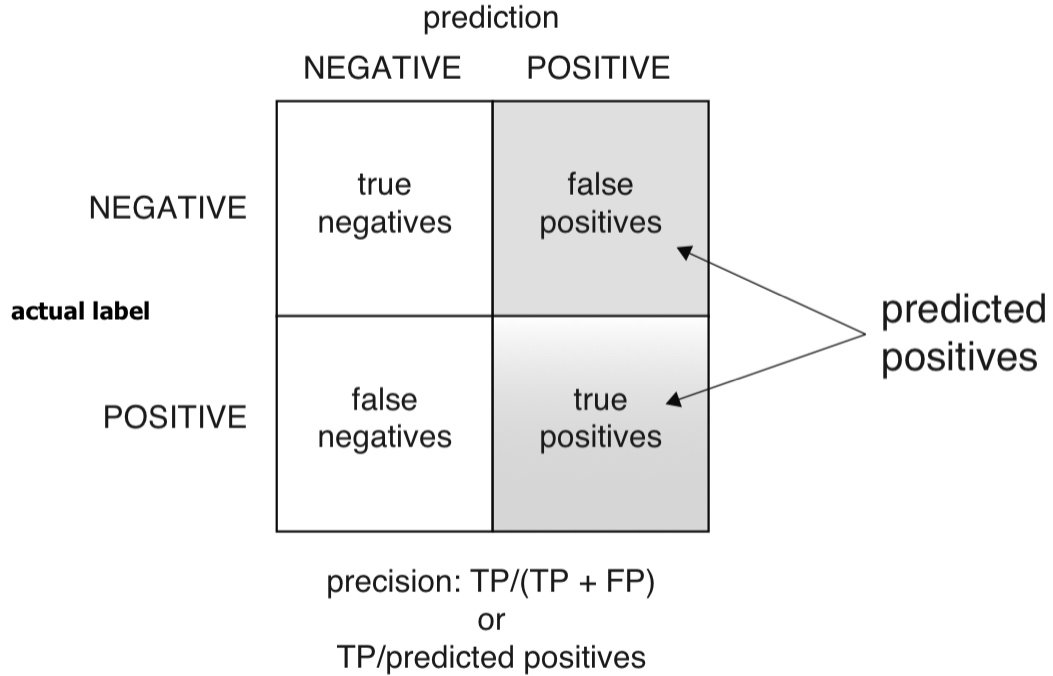

Precision

- Precision: If the classifier says this newborn baby is at risk, what’s the probability that the baby is really at risk?

- Precision is defined as the ratio of true positives to predicted positives.

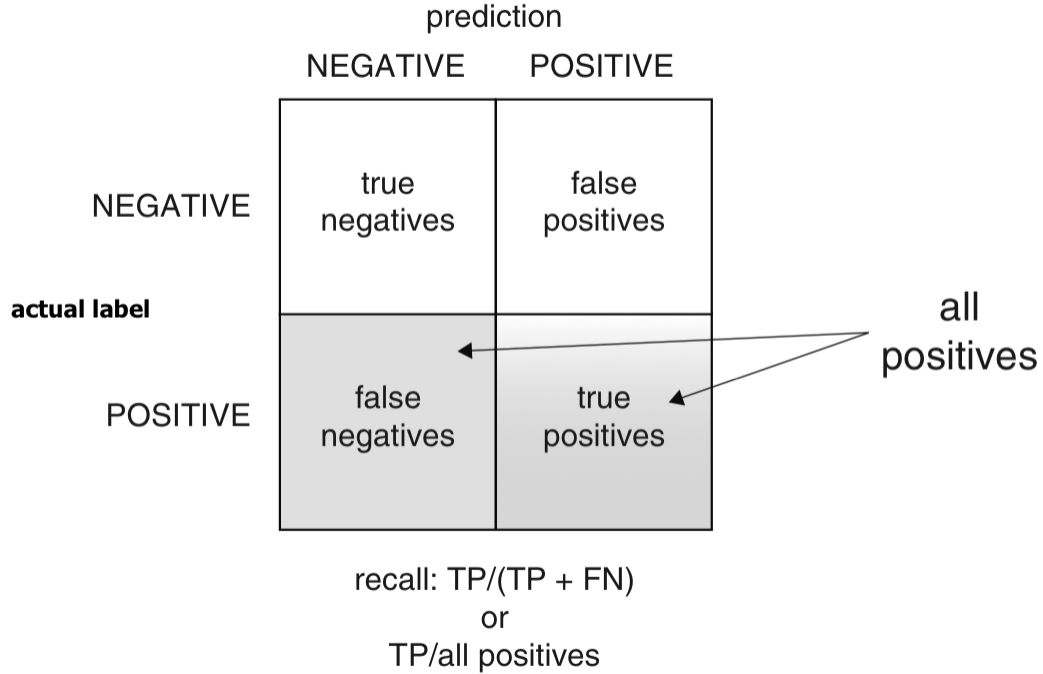

Recall (or Sensitivity)

- Recall (or sensitivity): Of all the babies at risk, what fraction did the classifier detect?

- Recall (or sensitivity) is also called the true positive rate (TPR), the ratio of true positives over all actual positives.

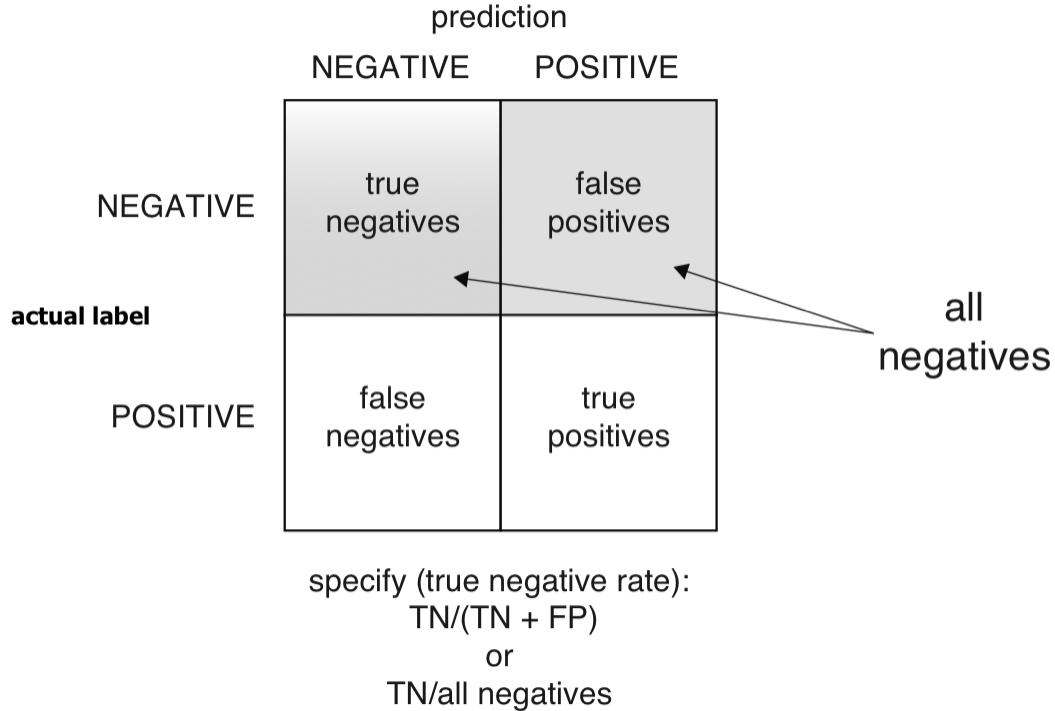

Specificity

- Specificity: Of all the not-at-risk babies, what fraction did the classifier detect?

- Specificity is also called the true negative rate (TNR), the ratio of true negatives over all actual negatives.

Enrichment

- Average: Average rate of new born babies being at risk

- Enrichment: How does the classifier precisely choose babies at risk relative to the average rate of new born babies being at risk?

- We want a classifier whose enrichment is greater than 2.

- There is a trade-off between recall and precision/enrichment.

- There is also a trade-off between recall and specificity.

- What would be the optimal threshold?

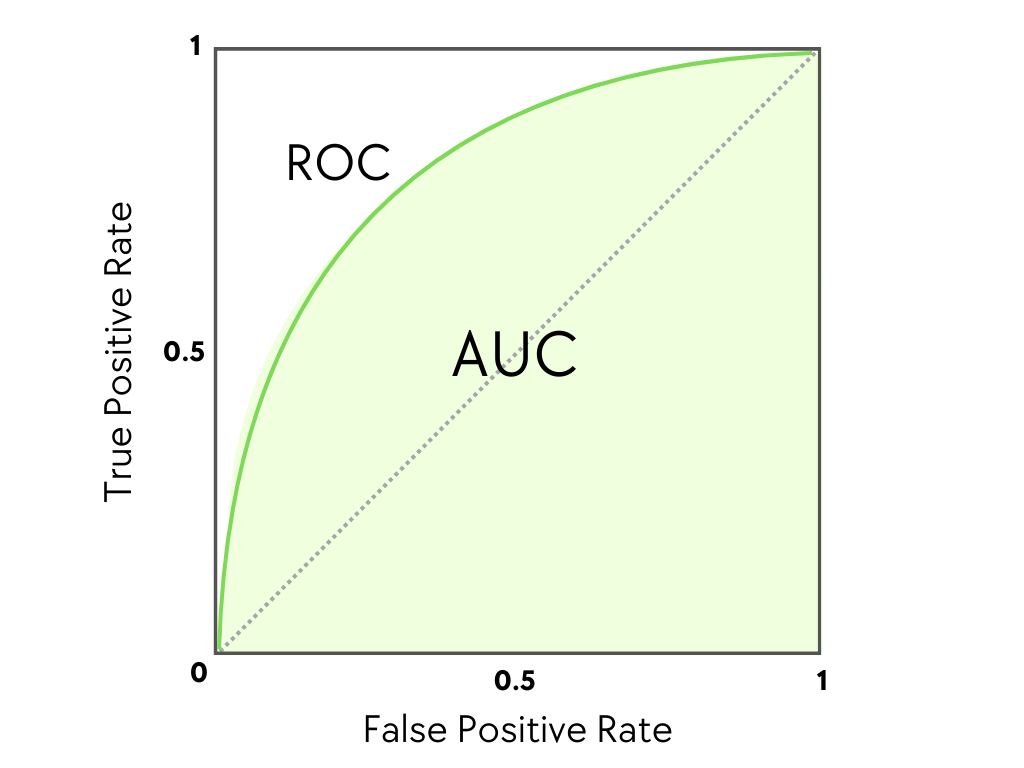

ROC and AUC

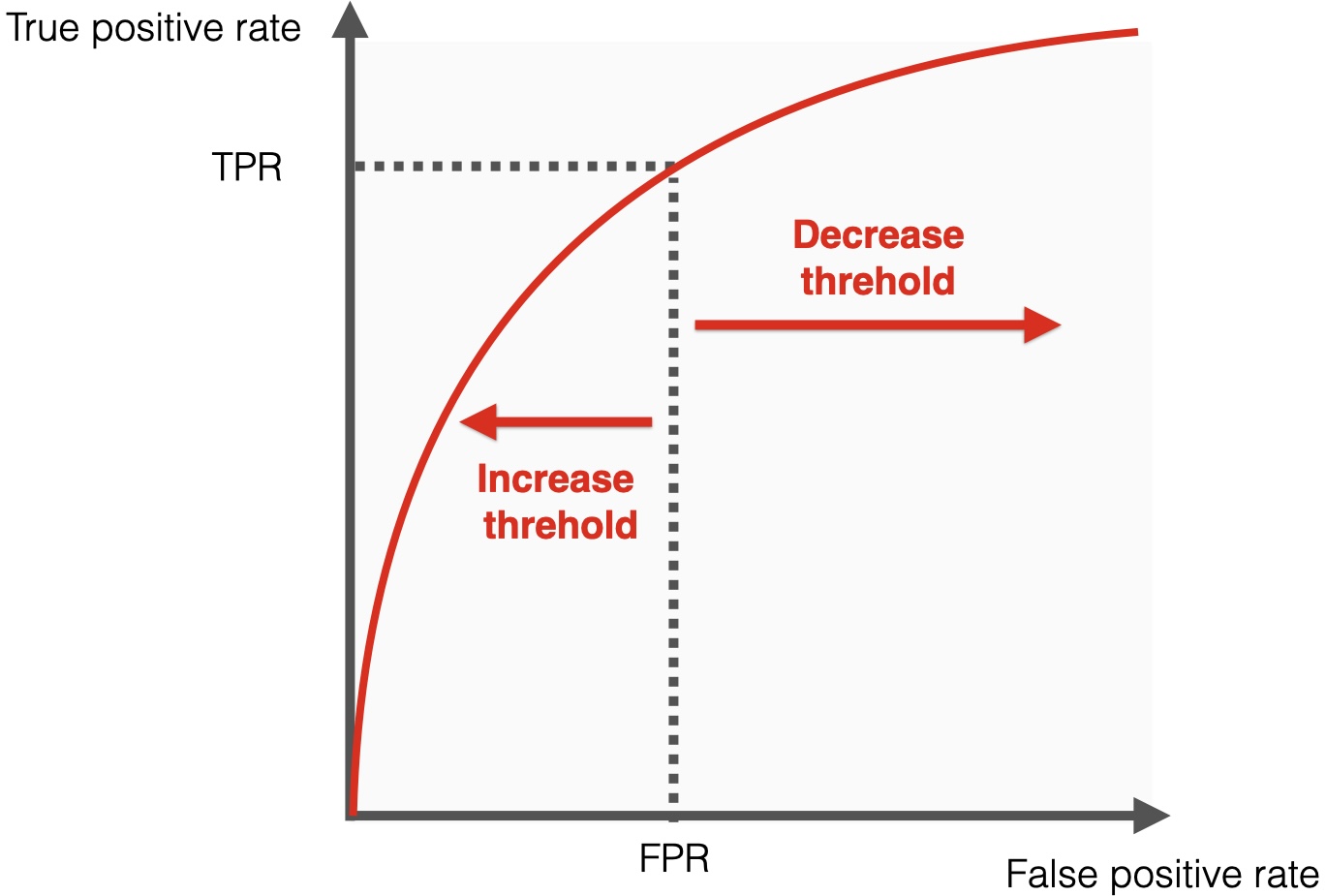

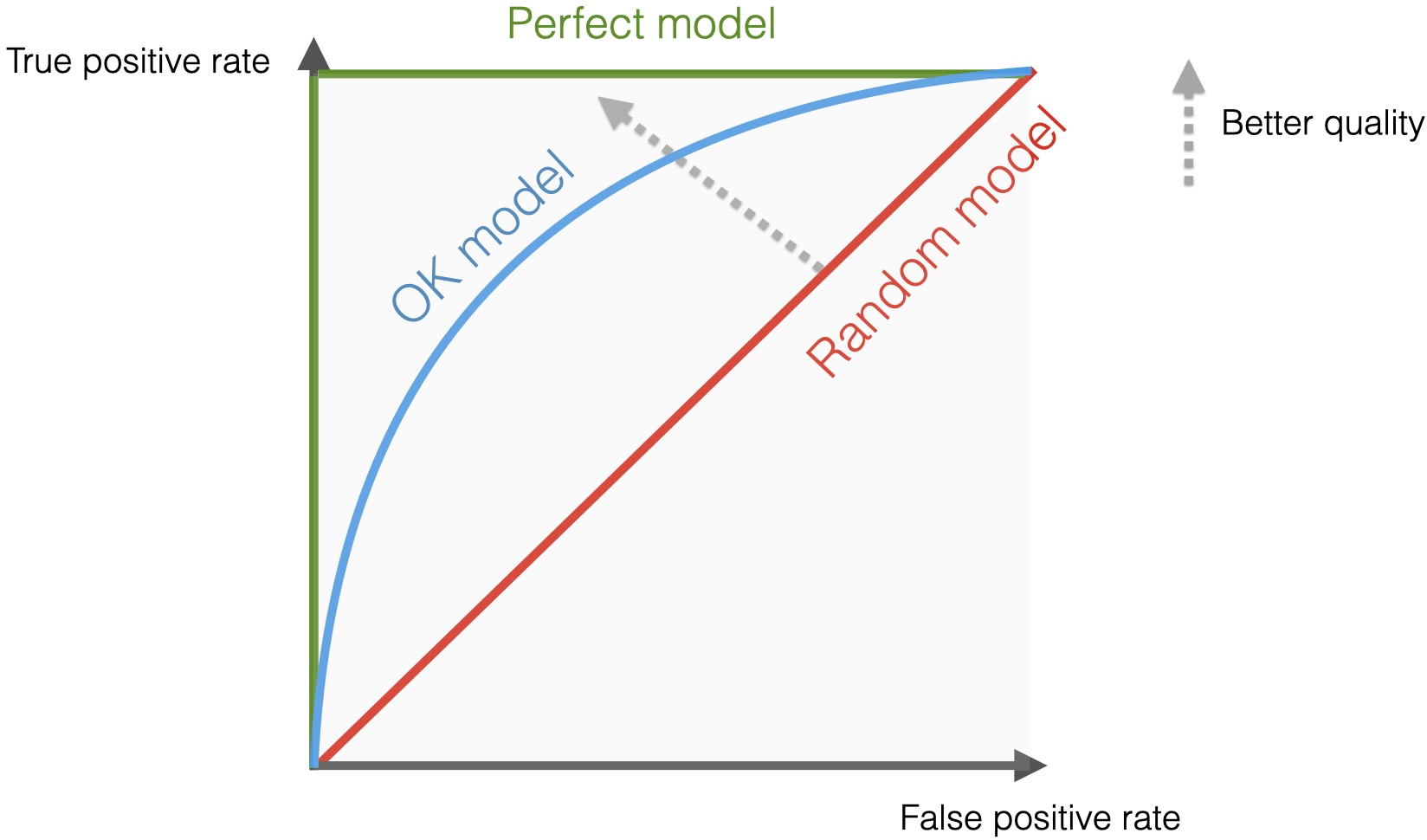

The receiver operating characteristic curve (or ROC curve) plots both the true positive rate (recall) and the false positive rate (or 1 - specificity) for all threshold levels.

- Area under the curve (or AUC) can be another measure of the quality of the model.

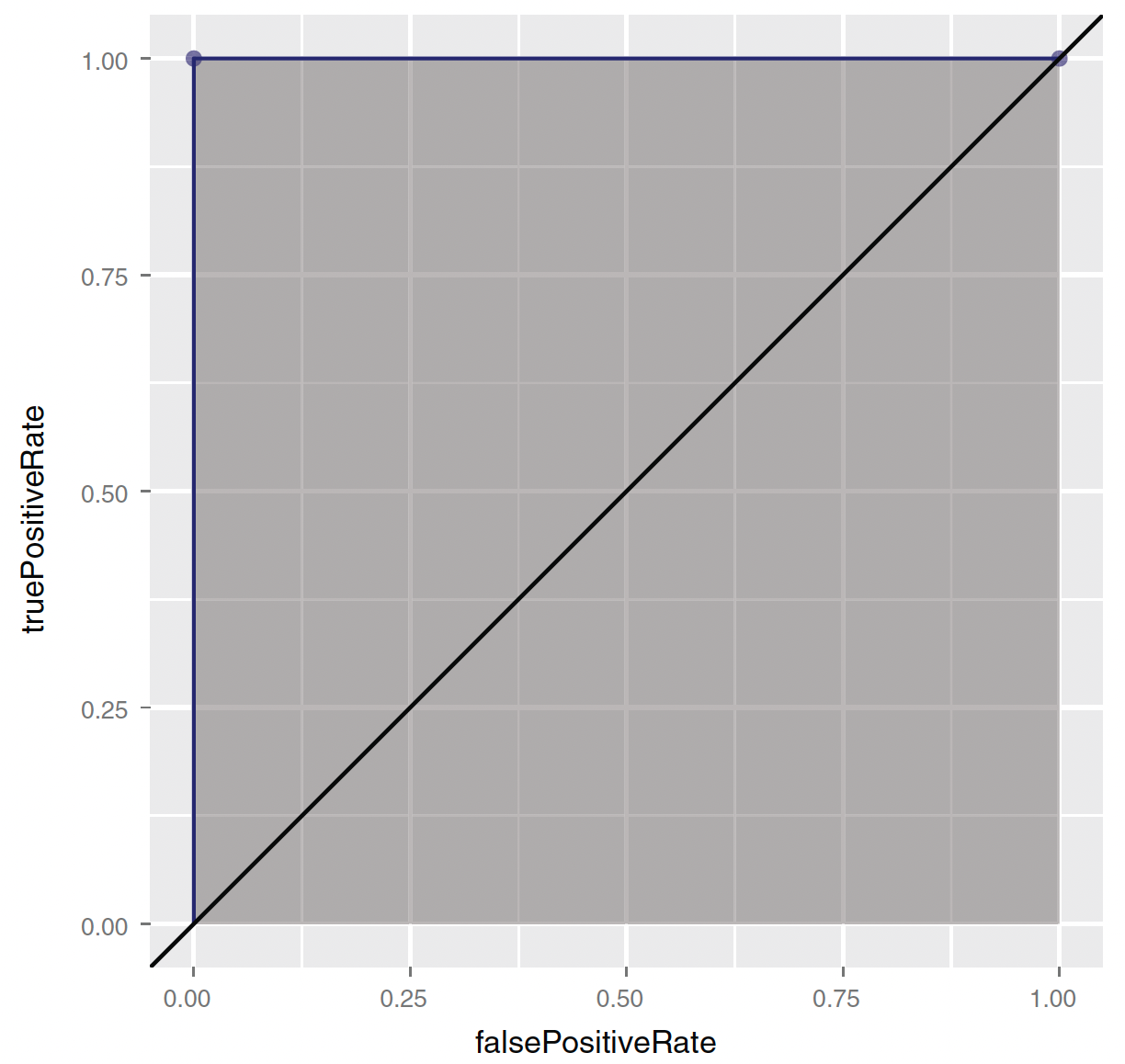

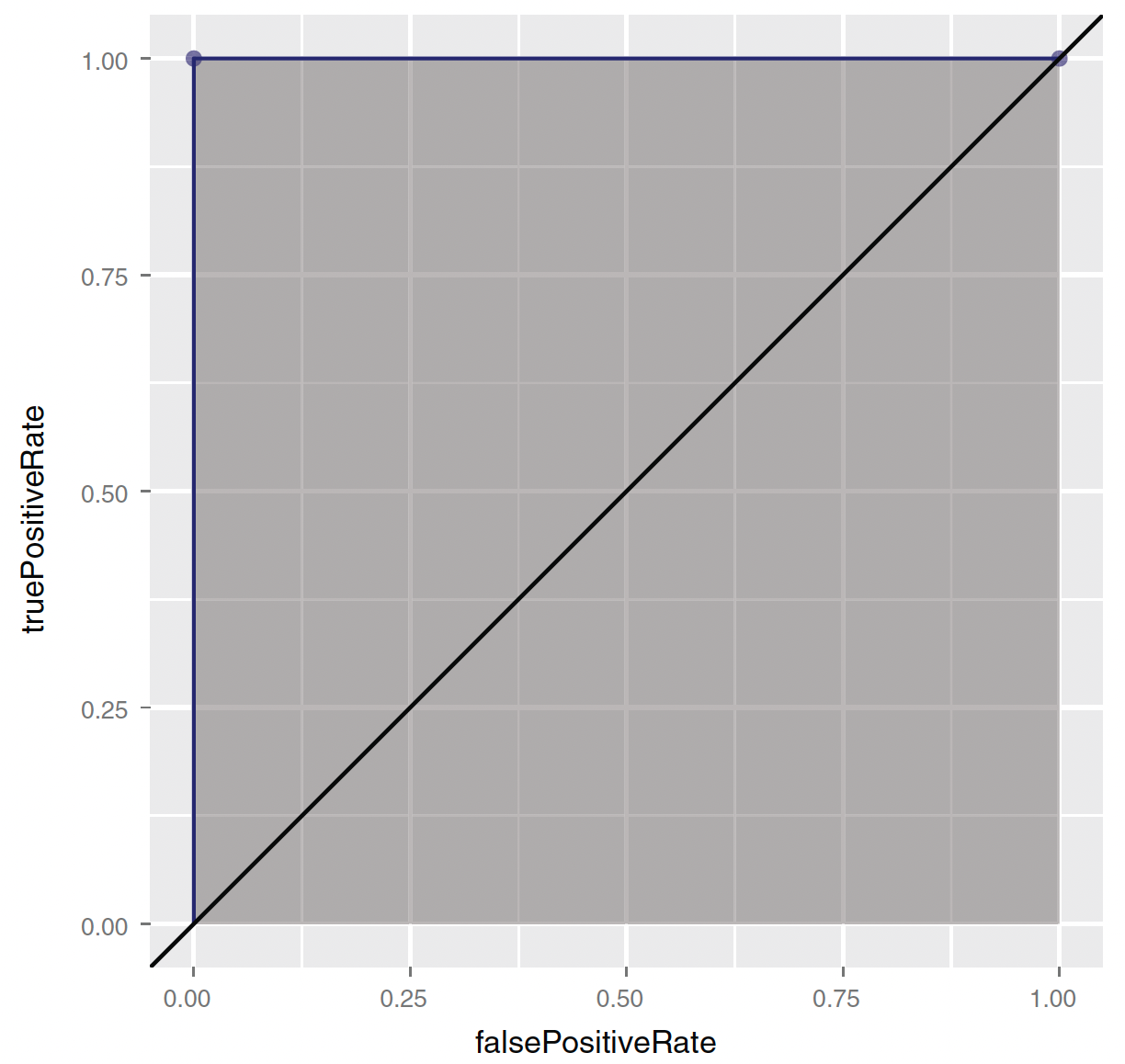

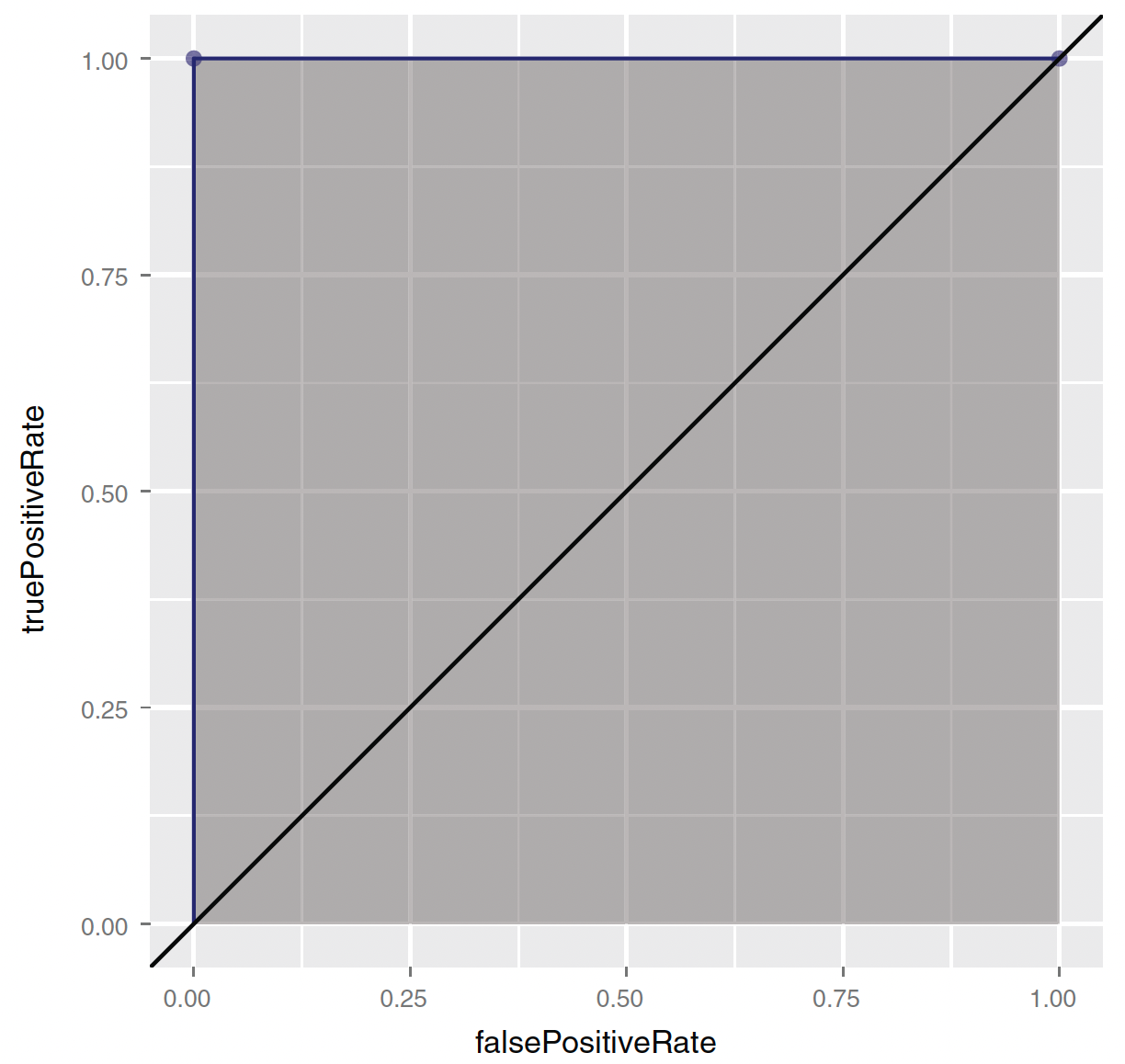

ROC - (0,0)

- (0,0)—Corresponding to a classifier defined by the threshold \(\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1) = 1\):

- Nothing gets classified as at-risk.

ROC - (1,1)

- (1,1)—Corresponding to a classifier defined by the threshold \(\text{Prob}(y_{i} = 1) = 0\):

- Everything gets classified as at-risk.

ROC - (0,1)

- (0,1)—Corresponding to any classifier defined by a threshold between 0 and 1:

- Everything is classified perfectly!

ROC and Thresholds

AUC

- AUC measures overall performance across all thresholds, with 1.0 being perfect.

Performance of Classifier

- Which classifier do you prefer for identifying at-risk babies?

- High accuracy, low recall, other things being equal;

- Low accuracy, high recall, other things being equal.

- Accuracy may not be a good measure for the classes that have unbalanced distribution of predicted probabilities (e.g., rare event).

Accuracy Can Be Misleading in Imbalanced Data

- Rare events (e.g., severe childbirth complications) occur in a very small percentage of cases (e.g., 1% of the population).

- A simple model that always predicts “not-at-risk” would be 99% accurate, as it correctly classifies 99% of cases where no complications occur.

- However, this does not mean the simple model is better—accuracy alone does not capture the effectiveness of a model when class distributions are skewed.

- A better model that identifies 5% of cases as “at-risk” and catches all true at-risk cases may appear to have lower overall accuracy than the simple model.

- Missing a severe complication (false negative) can be more costly than mistakenly flagging a healthy case as at risk (false positive).

Separation and Quasi-separation

What is Separation?

- One of the model variables or some combination of the model variables predicts the outcome perfectly for at least a subset of the training data.

- You’d think this would be a good thing; but, ironically, logistic regression fails when the variables are too powerful.

- Separation occurs when a predictor (or combination of predictors) perfectly separates the outcome classes.

- For example, if:

- All

fail = TRUEwhensafety = low, and - All

fail = FALSEwhensafety ≠ low,

then the model can predict the outcome with 100% accuracy based onsafety.

- All

- ➡️ This leads to infinite (non-estimable) coefficients.

What is Quasi-Separation?

- Quasi-separation occurs when:

- Some, but not all, values of a predictor perfectly predict the outcome.

- Example:

fail = TRUEfor all cars withsafety = low,

- But

failis mixed forsafety = medorhigh.

- ➡️ Model still suffers from unstable coefficient estimates or high standard errors.