Lecture 3

Panel Data Models

January 28, 2026

👥📈 Panel Data Models

👥📈 Panel Data Models: POLS → FE → TWFE → RE

Learning goals

- Understand what panel data is (and why we love it)

- Compare Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects, Two-Way FE, and Random Effects

- Learn what variation each model uses and what it controls for

- Understand country-clustered standard errors (and why we need them)

What is Panel Data?

Panel data tracks the same units over multiple time periods:

- Unit (\(i\)): country (USA, Korea, India, …)

- Time (\(t\)): year (1990–2022, …)

Example (CO\(_2\) panel): - Outcome: CO\(_2\) emissions per capita - Unit ID: iso_code - Time ID: year

Tip

Panel data gives us two kinds of variation: - Between variation: differences across countries - Within variation: changes within a country over time

Why Use Panel Models (Not Only Pooled OLS)?

Pooled OLS can be misleading because it ignores unobserved country differences that don’t change much over time, such as:

- 🌍 geography / climate / natural resources

- 🏭 industrial structure and history

- 🏛️ institutions and regulation

- ⚡ energy infrastructure and technology path

- 🧑🤝🧑 culture and long-run lifestyle patterns

These factors can affect both

- emissions (or other outcomes) and

- GDP per capita (or other regressors)

➡️ That creates omitted variable bias when we use Pooled OLS.

🧠 Unobserved Heterogeneity (The Core Issue)

Suppose the true relationship includes an unobserved country component:

\[ y_{it} = \beta x_{it} + \underbrace{\alpha_i}_{\text{unobserved country trait}} + \epsilon_{it} \]

If we ignore \(\alpha_i\) and estimate Pooled OLS:

\[ y_{it} = \beta x_{it} + u_{it} \quad \text{where} \quad u_{it} = \alpha_i + \epsilon_{it} \]

⚠️ If \(Cov(\alpha_i, x_{it}) \neq 0\), then:

- \(x_{it}\) is correlated with the error term

- Pooled OLS is biased

Fixed Effects is designed to solve exactly this problem.

1️⃣ Pooled OLS (POLS)

Pooled OLS: Baseline Model

Model \[ y_{it} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{it} + \epsilon_{it} \]

Meaning

- We pretend the dataset is one big cross-section

- We ignore the panel structure (country identity)

Uses all variation

- between-country variation

- within-country variation

What POLS is Really Doing

When you estimate POLS, the slope \(\beta_1\) reflects a combination of:

- Cross-country differences (rich vs. poor countries)

- Within-country changes (one country over time)

So interpretation becomes:

“On average, countries with higher \(x\) have higher (or lower) \(y\), and/or when \(x\) rises over time, \(y\) moves…”

⚠️ That can be fine only if unobserved country traits don’t confound the relationship.

⚠️ The Big Risk in POLS: Omitted Variable Bias

If richer countries also have different institutions, energy systems, or historical industrialization paths, then:

- \(x_{it}\) (GDP per capita) is correlated with \(\alpha_i\) (unobserved traits)

- Pooled OLS mixes together the effect of \(x_{it}\) and the influence of \(\alpha_i\), so the estimated \(\beta\) can be misleading.

Panel methods help because they explicitly control for \(\alpha_i\).

2️⃣ Fixed Effects (FE)

Country Fixed Effects (FE)

Model \[ y_{it} = \beta x_{it} + \alpha_i + \epsilon_{it} \]

- \(\alpha_i\) = country fixed effect

- captures all time-invariant country characteristics

- geography, long-run institutions, baseline culture, etc.

FE answers a within-country question:

“If a country’s \(x\) changes over time, how does \(y\) change within that same country?”

🔎 What FE Controls For (Automatically)

Because each country gets its own intercept \(\alpha_i\), FE controls for:

- any factor that is constant within a country

- even if you do not observe or measure it

Examples (time-invariant or very slow-moving):

- distance to equator

- landlocked status

- baseline political system

- deep energy infrastructure

📌 FE is powerful because it controls for a lot without measuring those things.

FE Uses Only Within-Country Variation

FE does not use differences between countries:

- It does not compare USA vs India levels

- It compares USA over time to itself

So FE is best when:

- the key confounding problem is time-invariant

- we care about within-country causal interpretation

⚠️ FE cannot estimate effects of variables that do not change over time, e.g.:

landlocked,continent,distance_to_equator

3️⃣ Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE)

Two-Way Fixed Effects (Country + Year FE)

Model \[ y_{it} = \beta x_{it} + \alpha_i + \gamma_t + \epsilon_{it} \]

- \(\alpha_i\): country FE (time-invariant traits)

- \(\gamma_t\): year FE (global shocks / common trends)

TWFE answers:

“Within a country, how does \(y\) change with \(x\), after removing global year shocks?”

🌍 Why Add Year Fixed Effects?

Year effects capture shocks that hit many countries at once:

- 🛢️ oil price spikes

- 📉 global recessions (e.g., 2008)

- 🦠 pandemics

- 💡 global technology trends

- 🌐 global climate agreements

If we don’t include \(\gamma_t\), the regression may mistakenly attribute these common shocks to \(x_{it}\).

Year FE helps remove this confounding.

4️⃣ Random Effects (RE)

Random Effects (RE)

Model \[ y_{it} = \beta x_{it} + \alpha_i + \epsilon_{it} \]

Same structure as FE… but different assumption:

- RE treats \(\alpha_i\) as random

- and assumes it is uncorrelated with regressors:

\[ Cov(\alpha_i, x_{it}) = 0 \]

If that assumption holds:

- RE is more efficient than FE (smaller standard errors)

- RE uses both within and between variation

⚠️ When RE Fails (Bias Risk)

If \(Cov(\alpha_i, x_{it}) \neq 0\), then RE is biased.

In many economic settings, this correlation is very plausible:

- richer countries may also have better institutions (inside \(\alpha_i\))

- energy system differences affect both GDP and emissions

So FE is often the safer default in applied work.

🧠 Standard Errors in Panel Data

🧠 Why We Cluster Standard Errors (Country-Clustered SE)

The problem: errors are correlated within countries

In panel data, observations inside a country are rarely independent:

- shocks persist over time

- policies change gradually

- measurement errors repeat

- emissions and GDP move smoothly

That means residuals may satisfy serial correlation:

\[ Cov(\epsilon_{it}, \epsilon_{is}) \neq 0 \quad \text{for } t \neq s \]

If we ignore this, standard errors are often too small → false “significance”

Cluster-Robust Standard Errors (by Country)

Country-clustered SEs allow:

- arbitrary correlation over time within a country

- heteroskedasticity across countries

Interpretation:

“We allow any kind of serial correlation within each country.”

In R (plm), this is typically implemented using robust VCOV options, e.g. vcovHC() with clustering by group.

vcovHC: variance–covariance, heteroskedasticity-consistent

Model Summary (What Each One Controls For)

| Model | Controls for country traits? | Controls for year shocks? | Uses between-country variation? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled OLS | ❌ No | ❌ No | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes (time-invariant) | ❌ No | ❌ No |

| Two-way FE | Yes (time-invariant) | Yes | ❌ No |

| Random Effects | Yes (modeled as random intercept) | Optional | Yes |

Final Takeaway (Panel Models)

We use panel data models to estimate relationships within units over time, while controlling for:

- hidden country characteristics (\(\alpha_i\))

- global year shocks (\(\gamma_t\))

And we use clustered SEs because panel residuals are often correlated within each unit.

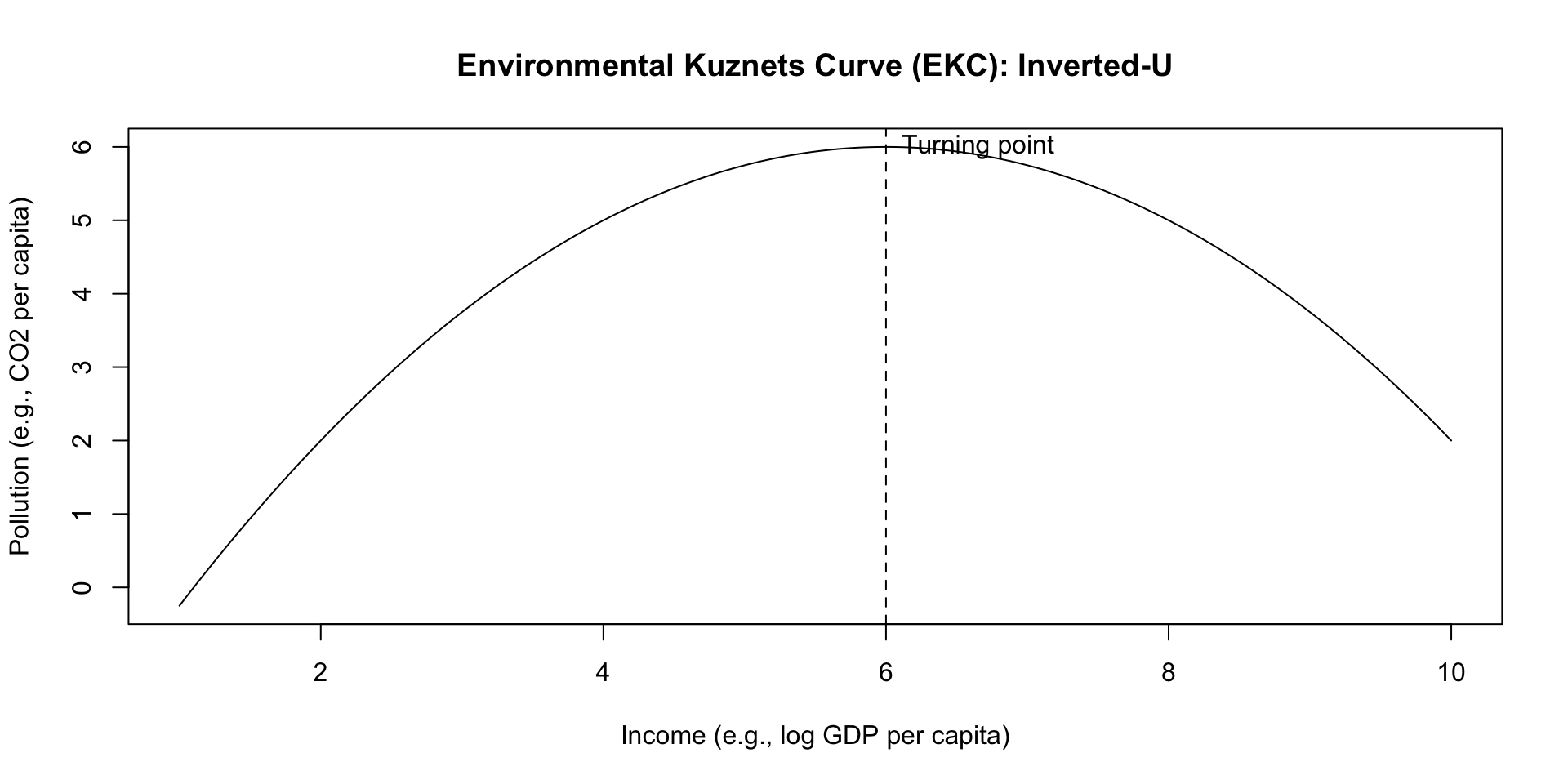

🌿 Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC): Growth vs. Pollution

🌿 Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC): Growth vs. Pollution

Now we add the key EKC idea:

What is the EKC?

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis suggests:

As a country becomes richer, pollution first increases,

but after some income level, pollution decreases.

It is often described as an inverted-U relationship between:

- pollution (e.g., CO\(_2\) per capita)

- income (GDP per capita)

📉📈 Draw the EKC Curve (Inverted-U)

Intuition: Why Might EKC Happen?

As income rises, countries often experience:

- Scale effect 📈: more production → more emissions (early stage)

- Composition effect 🏗️➡️🧑💼: shift from industry → services (middle stage)

- Technique effect 🧪⚡: cleaner technology + regulation (later stage)

EKC is the balance of:

- growth pressures that increase emissions

- development forces that can reduce emissions

Important Caveat for CO\(_2\)

EKC may be weaker for CO\(_2\) than for local air pollutants because:

- CO\(_2\) is deeply tied to energy systems

- benefits are global, costs are often local

- emissions may shift across borders via trade (carbon leakage)

So EKC is a hypothesis to test, not a guaranteed pattern.

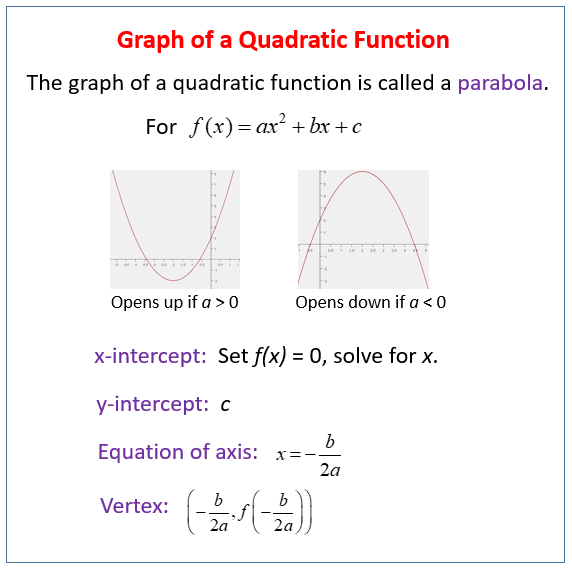

💡Quick Review: Graph for a Quadratic Function

EKC Panel Regression (Country-Year Data)

A common EKC specification:

\[ \log(CO2pc_{it}) = \beta_1 \log(GDPpc_{it}) + \beta_2 \left[\log(GDPpc_{it})\right]^2 + \alpha_i + \gamma_t + \epsilon_{it} \]

- \(i\): country

- \(t\): year

- \(\alpha_i\): country fixed effects

- \(\gamma_t\): year fixed effects

How to Interpret EKC Coefficients

If \(\beta_1 > 0\) and \(\beta_2 < 0\)

emissions rise at first, then eventually fall

→ EKC pattern (inverted-U)If \(\beta_2 = 0\)

→ relationship is linearIf \(\beta_2 > 0\)

→ U-shape (emissions accelerate with income)

EKC Turning Point (Income Level)

The turning point occurs where the slope becomes zero:

\[ \frac{\partial \log(CO2pc)}{\partial \log(GDPpc)} = \beta_1 + 2\beta_2 \log(GDPpc) = 0 \]

So the turning point in log income is:

\[ \log(GDPpc^*) = -\frac{\beta_1}{2\beta_2} \]

Convert back to the income level:

\[ GDPpc^* = \exp\left(-\frac{\beta_1}{2\beta_2}\right) \]

At \(GDPpc^*\), CO\(_2\) per capita stops rising and begins falling (if EKC holds).

Final Takeaway (EKC)

EKC tests whether pollution follows an inverted-U with income.

Panel FE/TWFE help make that test more credible by controlling for:

- country traits (\(\alpha_i\))

- year shocks (\(\gamma_t\))