Lecture 2

Linear Regression

January 26, 2026

Big Data and Machine Learning

Big Data and Machine Learning (ML)

- The term “Big Data” originated from computer scientists working with datasets too large to fit on a single machine.

- As aggregation evolved into analysis, Big Data became closely linked with statistics and machine learning (ML).

- Scalability of algorithms is crucial for handling large datasets.

- We will use ML to:

- ✅ Identify patterns in big data

- ✅ Make data-driven decisions

What does it mean to be “big”?

Big in both the number of observations (size

n) and in the number of variables (dimensionp).In these settings, we cannot:

- Look at each individual variable and make a decision.

- Choose among a small set of candidate models.

- Plot every variable to look for interactions or transformations.

Some ML tools are straight out of previous statistics classes (linear regression) and some are totally new (ensemble models, principal component analysis).

- All require a different approach when

nandpget really big.

- All require a different approach when

ML topics

- Regression: inference and prediction

- Regularization: cross-validation

- Principal Component Analysis: dimension reduction

- Tree-based models: decision trees, random forest, XGBoost

- Classfication: kNN

- Clustering: k-means, association rules

- Text Mining: sentiment analysis; topic models

- Deep learning: deep neural networks

Linear Regression Model

Linear Model

Linear regression assumes a linear relationship for \(Y = f(X_{1})\): \[Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i} \,+\, \epsilon_{i}\] for \(i \,=\, 1, 2, \dots, n\), where \(i\) is the \(i\)-th observation in data.

\(Y_i\) is the \(i\)-th value for the outcome/dependent/response/target variable \(Y\).

\(X_{1, i}\) is the \(i\)-th value for the explanatory/independent/predictor/input variable or feature \(X_{1}\).

Beta Coefficients

Linear regression assumes a linear relationship for \(Y = f(X_{1})\): \[Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i} \,+\, \epsilon_{i}\] for \(i \,=\, 1, 2, \dots, n\), where \(i\) is the \(i\)-th observation in data.

\(\beta_0\) is an unknown true value of an intercept: average value for \(Y\) if \(X_{1} = 0\)

\(\beta_1\) is an unknown true value of a slope: increase in average value for \(Y\) for each one-unit increase in \(X_{1}\)

Random Noises

Linear regression assumes a linear relationship for \(Y = f(X_{1})\): \[Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i} \,+\, \epsilon_{i}\] for \(i \,=\, 1, 2, \dots, n\), where \(i\) is the \(i\)-th observation in data.

\(\epsilon_i\) is a random noise, or a statistical error: \[ \epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2) \]

- Errors have a mean value of 0 with constant variance \(\sigma^2\).

- Errors are uncorrelated with \(X_{1, i}\). \[ Y_i \sim N(\,\beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i}, \sigma^2\,) \]

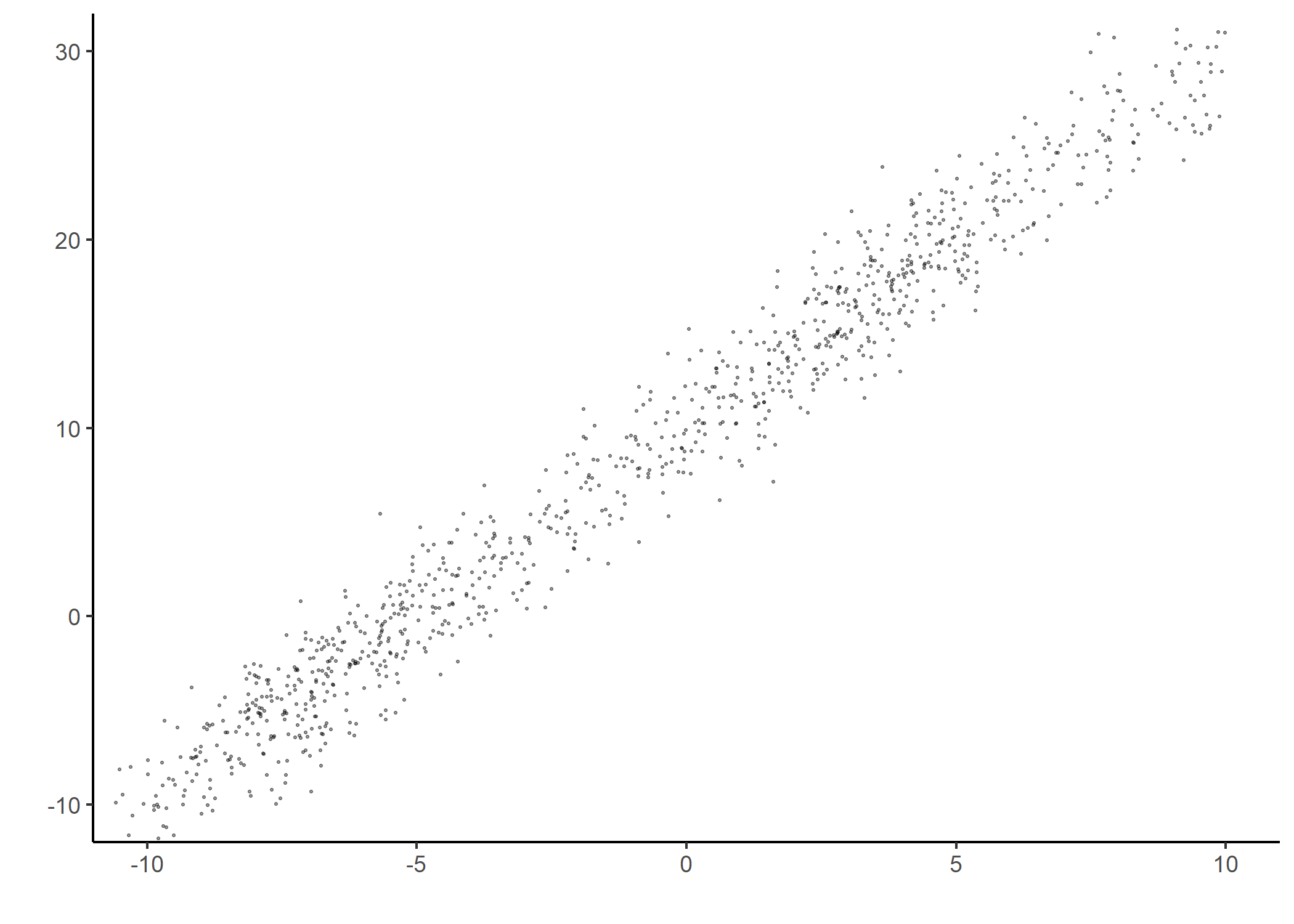

Random Noises

Random Noises

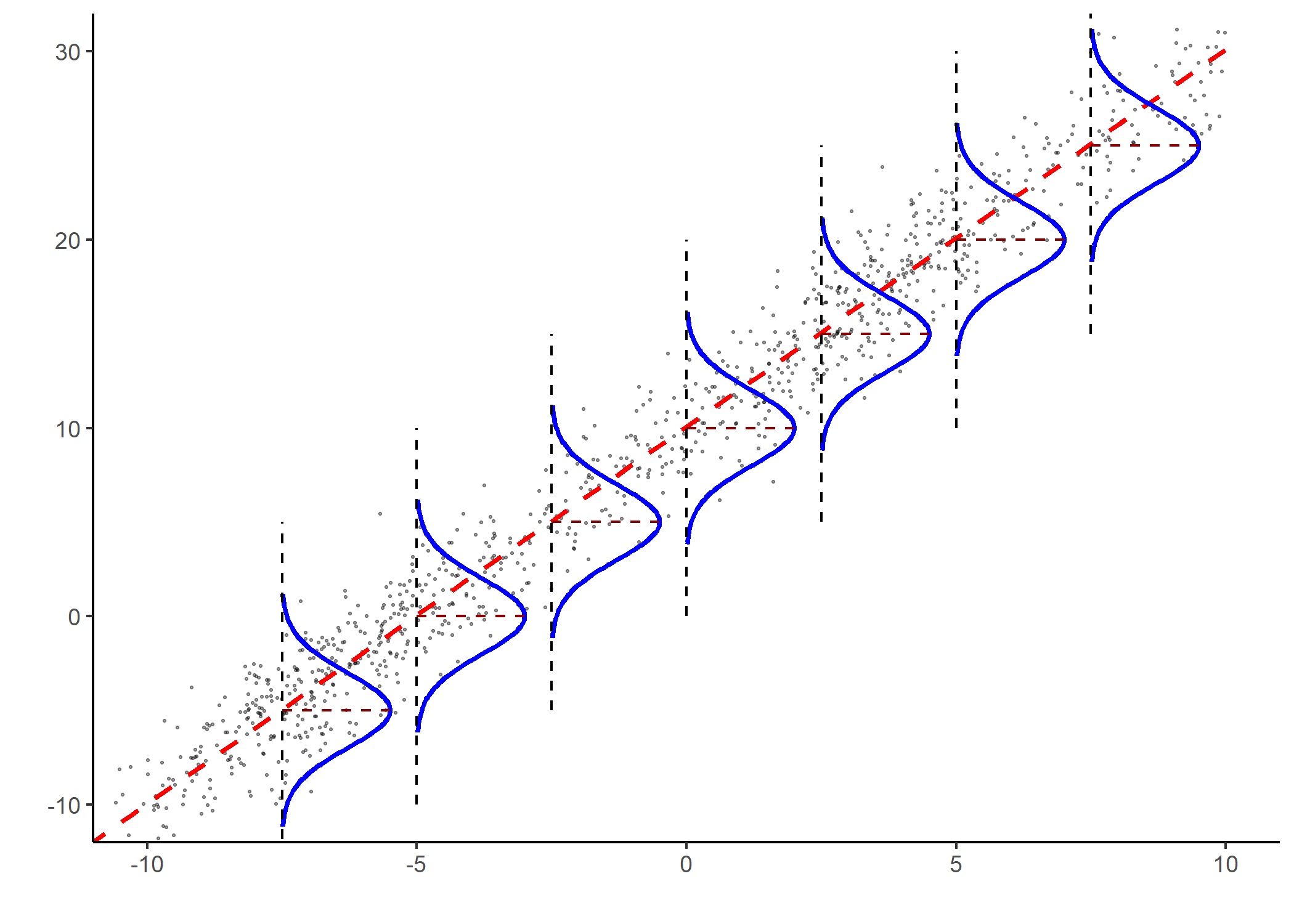

Best Fitting Line

Linear regression finds the beta estimates \(( \hat{\beta_{0}}, \hat{\beta_{1}} )\) such that:

– The linear function \(f(X_{1}) = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1}\) is as near as possible to \(Y\) for all \((X_{1, i}\,,\, Y_{i})\) pairs in the data.

- It is the best fitting line, or the predicted outcome, \(\hat{Y_{\,}} = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1}\).

Residual Errors

- The estimated beta coefficients are chosen to minimize the sum of squares of the residual errors \((SSR)\): \[ \begin{align} SSR &\,=\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{1})^{2}\\ &\quad \,+\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{2})^{2}\\ &\quad\,+\, \cdots + (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{n})^{2}\\ \text{where}\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad&\\ \texttt{Residual_Error}_{i} &\,=\, Y_{i} \,-\, \hat{Y_{i}},\\ \texttt{Predicted_Outcome}_{i}: \hat{Y_{i}} &\,=\, \hat{\beta_{0}} \,+\, \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1, i} \end{align} \]

Hat Notation

We use the hat notation \((\,\hat{\texttt{ }_{\,}}\,)\) to distinguish true values and estimated/predicted values.

The value of true beta coefficient is denoted by \(\beta_{1}\).

The value of estimated beta coefficient is denoted by \(\hat{\beta_{1}}\).

The \(i\)-th value of true outcome variable is denoted by \(Y_{i}\).

The \(i\)-th value of predicted outcome variable is denoted by \(\hat{Y_{i}}\).

What Is Linear Regression Doing? — Relationship

1. Finding the relationship between \(X_{1}\) and \(Y\) \[\hat{\beta_{1}}\]: How is an increase in \(X_1\) by one unit associated with a change in \(Y\) on average?

- Positive? Negative? Independent?

- How strong?

Statistical Significance in Estimated Beta Coefficients

- What does it mean for a beta estimate \(\hat{\beta_{\,}}\) to be statistically significant at 5% level?

- It means that the null hypothesis \(H_{0}: \beta = 0\) is rejected for a given significance level 5%.

- “2 standard error rule” of thumb: The true value of \(\beta\) is 95% likely to be in the confidence interval \((\, \hat{\beta_{\,}} - 2 * \texttt{Std. Error}\;,\; \hat{\beta_{\,}} + 2 * \texttt{Std. Error} \,)\).

- The standard error tells us how uncertain our beta estimate is.

- We should look for the stars!

What Is Linear Regression Doing? — Prediction

2. Making a prediction on \(Y\): \[\hat{Y_{\,}}\] For unseen data point of \(X_1\), what is the predicted value of outcome, \(\hat{Y_{\,}}\)?

- Examples:

- For \(X_{1} = 2\), the predicted outcome is \(\hat{Y_{\,}} = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}} \times 2\).

- For \(X_{1} = 3\), the predicted outcome is \(\hat{Y_{\,}} = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}} \times 3\).

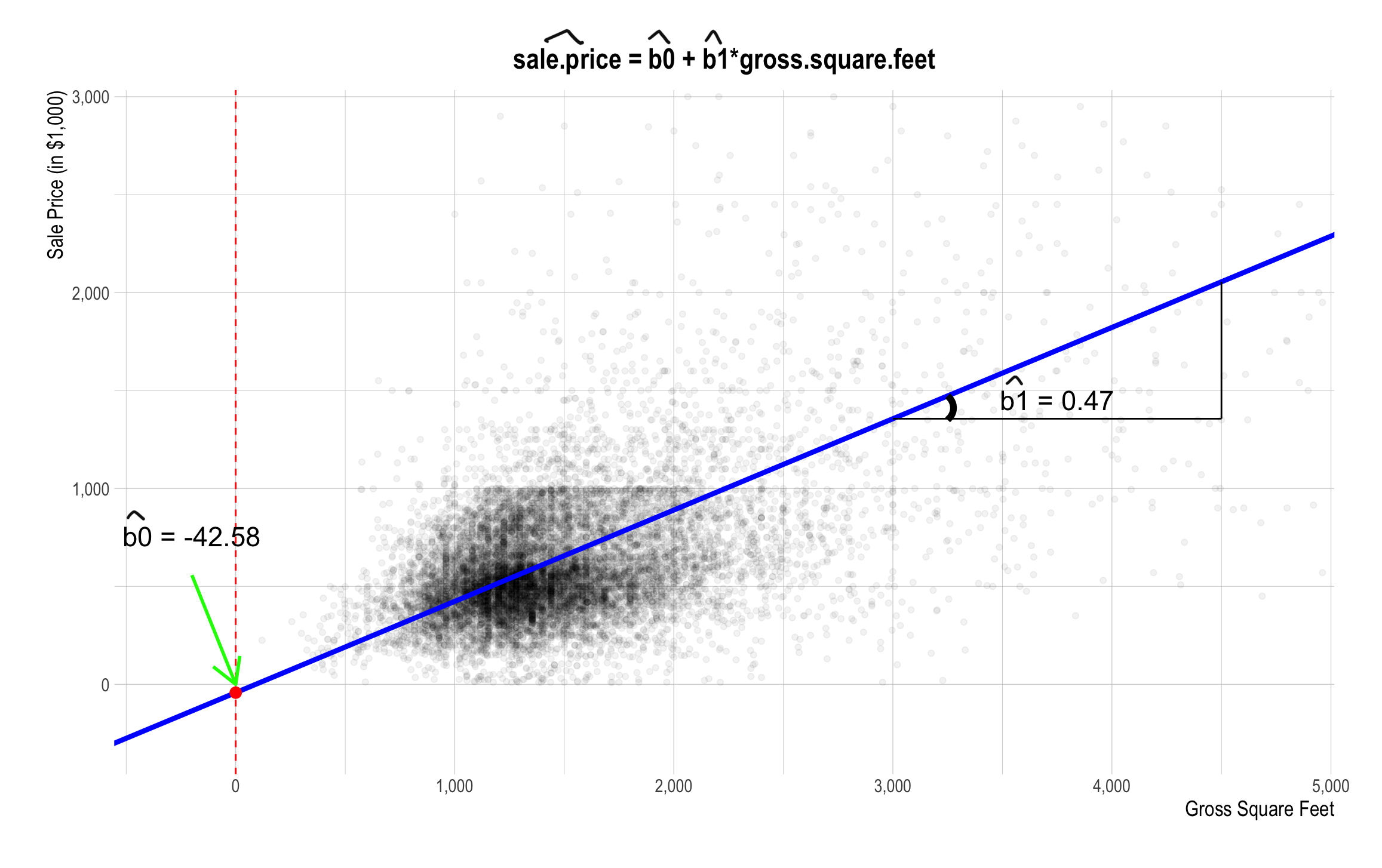

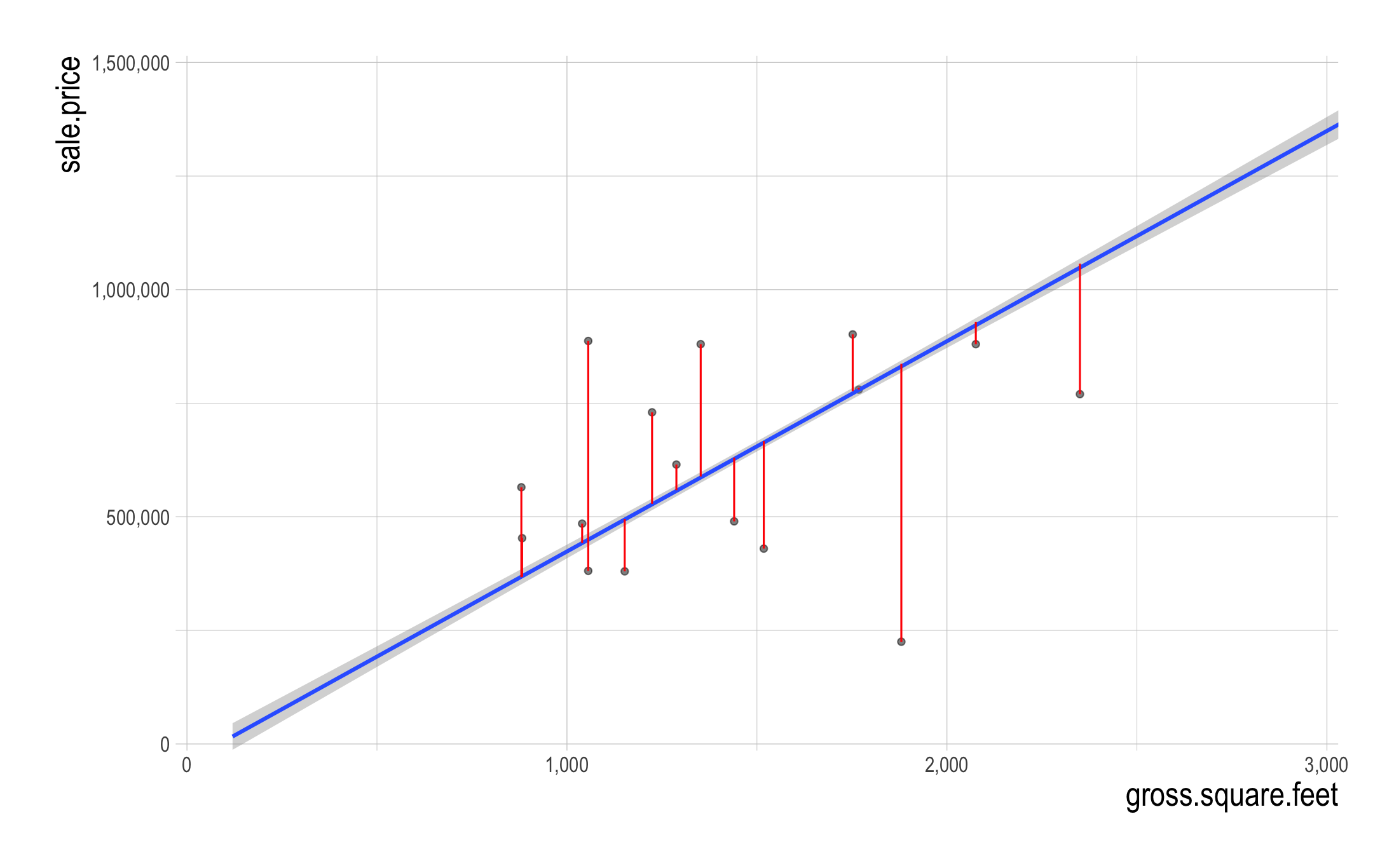

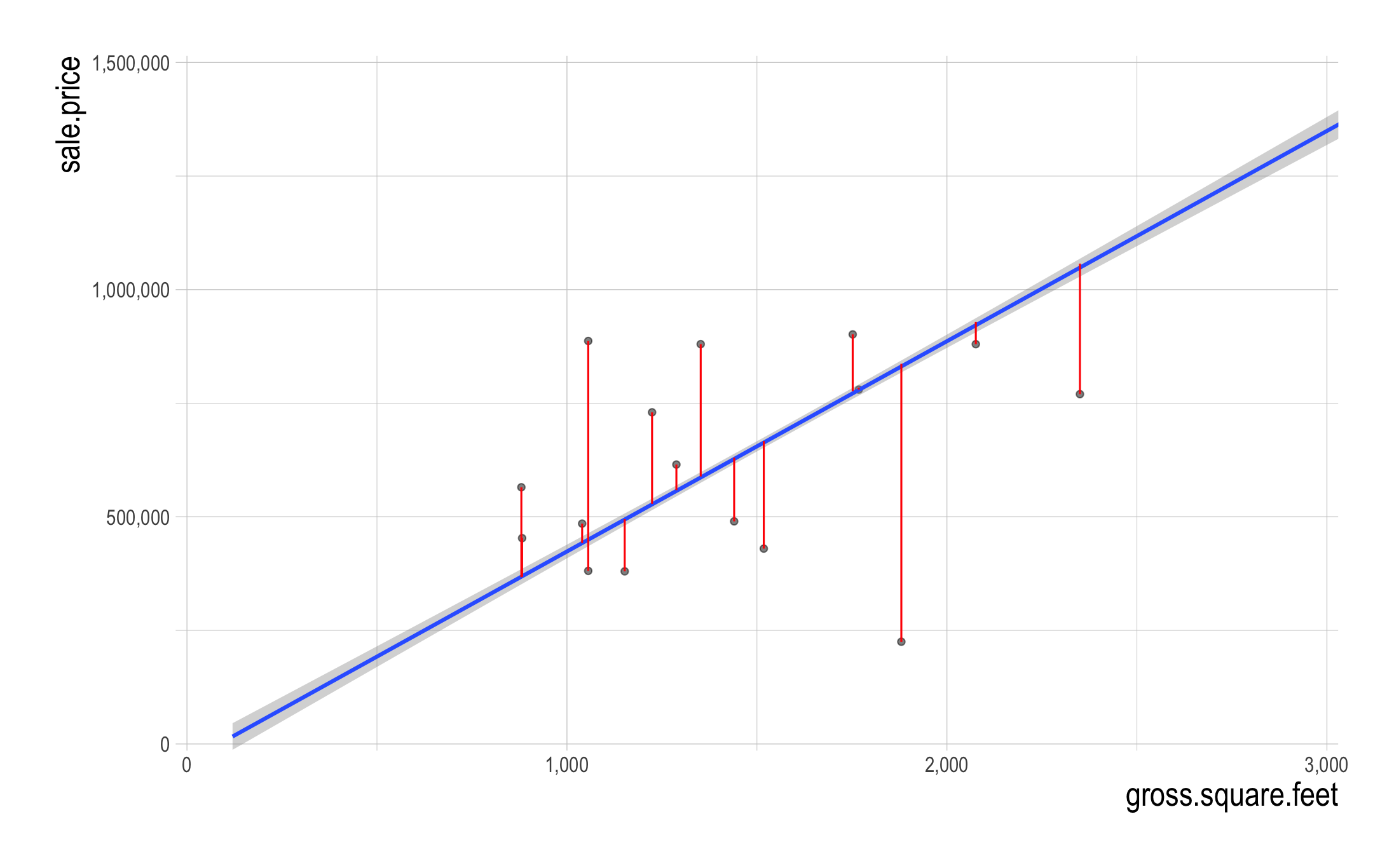

Linear Regression - Example

- Suppose we want to predict a property’s sales price based on the property size.

- In other words, for some house sale

i, we want to predictsale_price[i]based ongross_square_feet[i].

- In other words, for some house sale

- We also want to focus on the relationship between a property’s sales price and a property size.

- In other words, we estimate how an increase in

gross_square_feet[i]is associated withsale_price[i].

- In other words, we estimate how an increase in

Linear Relationship

\[\texttt{sale_price[i]} \;=\quad \texttt{b0} \,+\, \texttt{b1*gross_square_feet[i]} \,+\, \texttt{e[i]}\]

Linear regression assumes that:

- The outcome

sale_price[i]is linearly related to the inputgross_square_feet[i]:

- The outcome

where e[i] is a statistical error term.

The Linear Relationship between sale_price and gross_square_feet

Best Fitting Line

- What do the vertical lines visualize?

Model Evaluation — Mean squared error (MSE)

\[ \begin{align} MSE &= SSR\, / \, n\\ { }\\ SSR &\,=\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{1})^{2}\\ &\quad \,+\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{2})^{2}\\ &\quad\,+\, \cdots + (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{n})^{2} \end{align} \]

- One of the most common metrics used to measure the prediction accuracy of a linear regression model is MSE, which stands for mean squared error.

- \(MSE\) is \(SSR\) divided by \(n\) (the number of observations in the data that are used in making predictions).

- The lower MSE, the higher accuracy of the model.

- The root MSE (RMSE) is the square root of MSE.

Mean squared error (MSE)

- The root MSE (RMSE) represents the overall deviation of \(Y_{i}\) from the best fitting regression line.

Model Evaluation — R-squared

R-squared is a measure of how well the model “fits” the data, or its “goodness of fit.”

- R-squared can be thought of as what fraction of the

y’s variation is explained by the explanatory variables.

- R-squared can be thought of as what fraction of the

We want R-squared to be fairly large and R-squareds that are similar on testing and training.

Caution: R-squared will be higher for models with more explanatory variables, regardless of whether the additional explanatory variables actually improve the model or not.

Goals of Linear Regression

- The goals of linear regression are to:

- Modeling for explanation: Find the relationship between

gross_square_feetandsale_priceby estimating a true value ofb1.

- The estimated value of

b1is denoted by \(\hat{\texttt{b1}}\).

- Modeling for prediction: Make a prediction on

sale_price[i]for new propertyi

- The predicted value of

sale_price[i]is denoted by \(\widehat{\texttt{sale_price}}\texttt{[i]}\), where

\[\widehat{\texttt{sale_price}}\texttt{[i]} \;=\quad \hat{\texttt{b0}} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*gross_square_feet[i]}\]

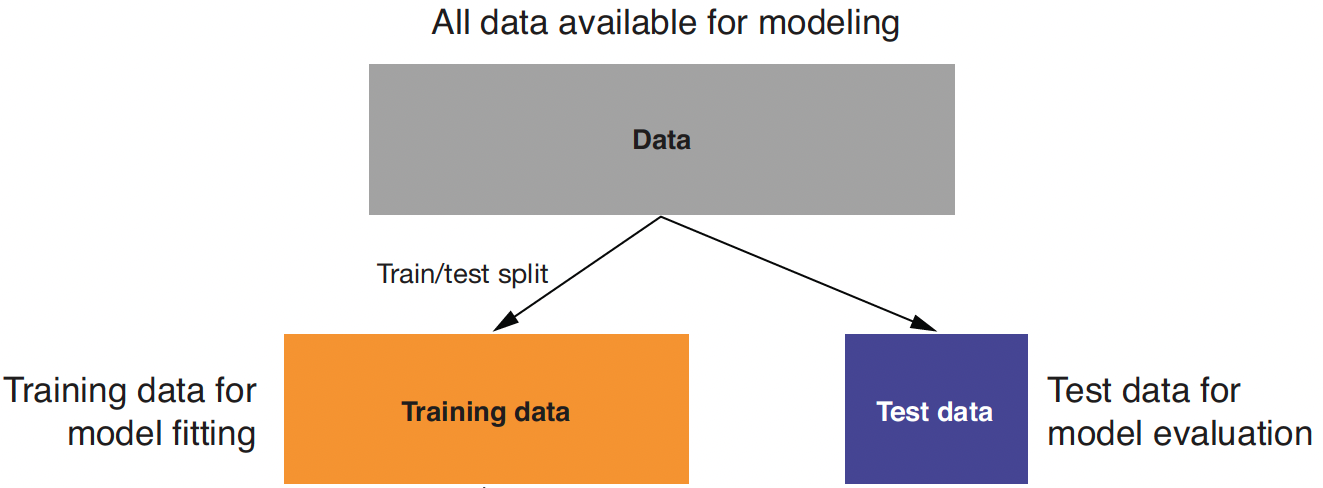

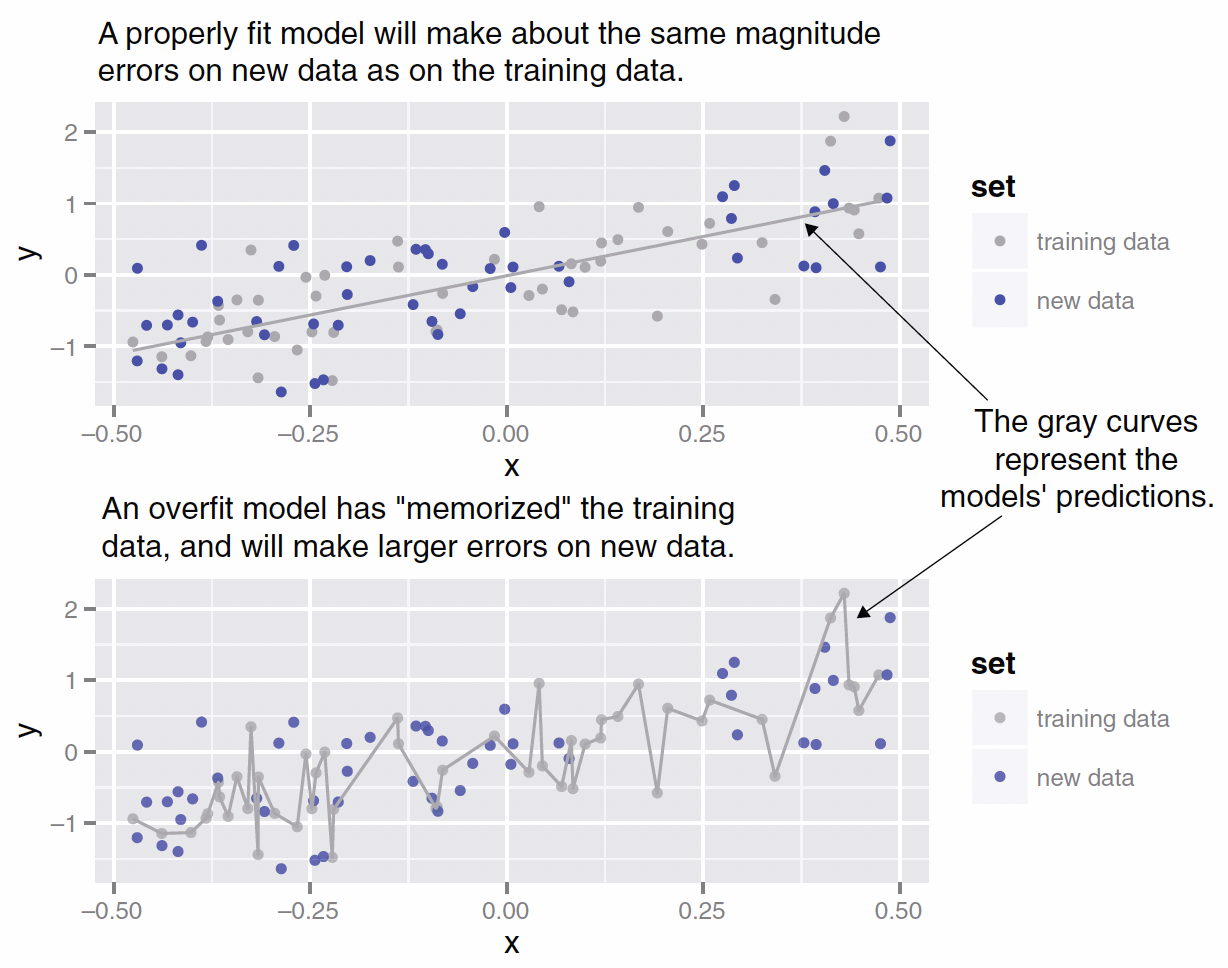

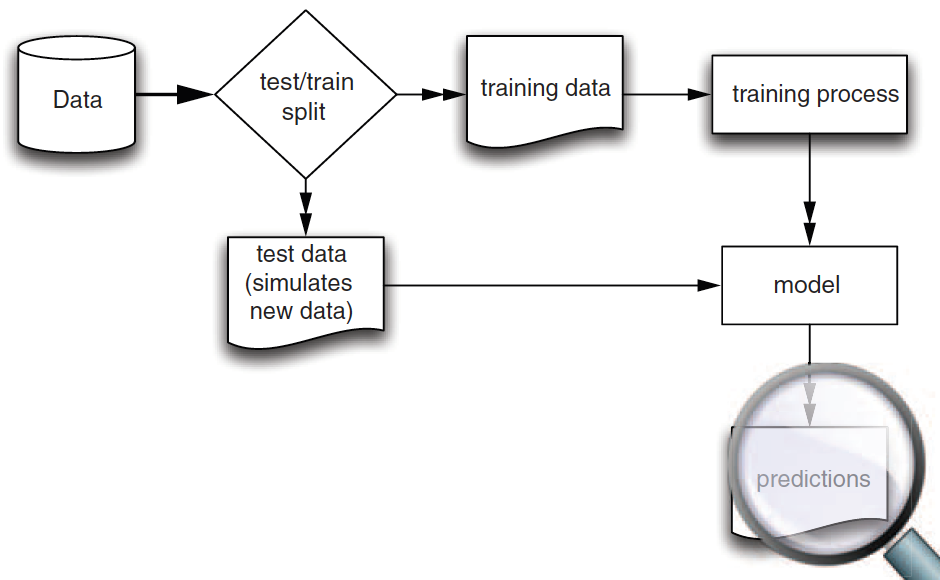

Training and Test Data

Training data: When we’re building a linear regression model, we need data to train the model.

Test data: We also need data to test whether the model works well on new data.

- So, we start with splitting a given data.frame into training and test data.frames when building a linear regression model.

Training vs. Test Data

- We use training data to train/fit the linear regression model.

- We then make a prediction using test data, which are unseen/new from the viewpoint of the trained linear regression model.

- In this way, we can test whether our model performs well in the real world, where unseen data points exist.

Overfitting

Model Construction and Evaluation

A Little Bit of Statistics for the Uniform Distribution

The probability density function for the uniform distribution looks like:

With the uniform distribution, any values of \(x\) between 0 and 1 is equally likely drawn.

- We will use the uniform distribution when splitting data into training and testing data sets.

Randomization in the Sampling Process

- Why do we randomize when splitting given data into training and test data?

- Randomizing the sampling process ensures that the training and test data sets are representative for the population data.

- If the sample does not properly represent the entire population, the model result is biased toward the sample.

- Suppose the splitting process is not randomized, so that the observations with

sale_price > 10^6are in the training data and the observations withsale_price <= 10^6are in the test data.- What would be the model result then?

Linear Regression using R

Example of Linear Regression using R

We will use the data for residential property sales from September 2017 and August 2018 in NYC.

Each sales data recorded contains a number of interesting variables, but here we focus on the followings:

sale_price: a property’s sales price;gross_square_feet: a property’s size;age: a property’s age;borough_name: a borough where a property is located.

Use summary statistics and visualization to explore the data.

Splitting Data into Training and Testing Data

Simple Linear Regression in R

Call:

lm(formula = sale_price ~ gross_square_feet, data = dtrain)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1677677 -208583 -41403 135661 8667468

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -36232.101 14615.843 -2.479 0.0132 *

gross_square_feet 460.373 8.957 51.400 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 461900 on 7640 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.2569, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2569

F-statistic: 2642 on 1 and 7640 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Regression Table with stargazer

Regression Table with stargazer

Predicting on Test Data

Linear Regression Model with Multiple Predictors

Multivariate Regression

- What if the model is missing something important?

- Prices differ across boroughs.

- Apartments and houses differ.

- Older houses may differ from newer houses.

- Add multiple explanatory variables: Multivariate Regression

Models and Assumptions

Linear regression assumes a linear relationship for \(Y = f(X_{1}, X_{2})\): \[Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i} \,+\,\beta_{2} X_{2, i} \,+\, \epsilon_{i}\] for \(i \,=\, 1, 2, \dots, n\), where \(i\) is the \(i\)-th observation in data.

\(\beta_0\) is an unknown true value of an intercept: average value for \(Y\) if \(X_{1} = 0\) and \(X_{2} = 0\)

\(\beta_1\) is an unknown true value of a slope: increase in average value for \(Y\) for each one-unit increase in \(X_{1}\)

\(\beta_2\) is an unknown true value of a slope: increase in average value for \(Y\) for each one-unit increase in \(X_{2}\)

Random Noises

Linear regression assumes a linear relationship for \(Y = f(X_{1}, X_{2})\): \[Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1} X_{1, i}\,+\, \beta_{1} X_{2, i} \,+\, \epsilon_{i}\] for \(i \,=\, 1, 2, \dots, n\), where \(i\) is the \(i\)-th observation in data.

\(\epsilon_i\) is a random noise, or a statistical error: \[ \epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2) \]

- Errors have a mean value of 0 with constant variance \(\sigma^2\).

- Errors are uncorrelated with predictors.

Best Fitting Plane

- Linear regression finds the beta estimates \(( \hat{\beta_{0}}, \hat{\beta_{1}}, \hat{\beta_{2}} )\) such that:

- The linear function \(f(X_{1}, X_{2}) = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1} + \hat{\beta_{2}}X_{2}\) is as near as possible to \(Y\) for all \((X_{1, i}\,,\,X_{2, i}\,,\, Y_{i})\) pairs in the data.

- It is the best fitting plane, or the predicted outcome, \(\hat{Y_{\,}} = \hat{\beta_{0}} + \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1} + \hat{\beta_{2}}X_{2}\)

Residual Errors

- The estimated beta coefficients are chosen to minimize the sum of squares of the residual errors \((SSR)\): \[ \begin{align} SSR &\,=\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{1})^{2}\\ &\quad \,+\, (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{2})^{2}\\ &\quad\,+\, \cdots + (\texttt{Residual_Error}_{n})^{2}\\ \text{where}\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad&\\ \texttt{Residual_Error}_{i} &\,=\, Y_{i} \,-\, \hat{Y_{i}},\\ \texttt{Predicted_Outcome}_{i}: \hat{Y_{i}} &\,=\, \hat{\beta_{0}} \,+\, \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1, i} \,+\, \hat{\beta_{2}}X_{2, i} \end{align} \]

Multivariate Regression - Best Fitting Plane

- All else being equal, an increase in

gross_square_feetby one unit is associated with an increase insale_priceby \(\hat{\beta_{1}}\).

Multivariate Regression in R

Dummy Variables in Linear Regression

Motivation: Treating Categorical Variables in Linear Regression

Linear regression models require numerical predictors, but many variables are categorical.

- Example: same house characteristics but different boroughs.

The Approach:

Convert categorical variables into numerical format using dummy variables.Why Do This?

- Allows the model to compare different categories.

- Each dummy variable indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of a category.

What are Dummy Variables?

Definition: Binary indicators (0 or 1) representing categories.

Purpose: Transform qualitative data into a quantitative form for regression analysis.

Example: \[ D_i = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if the observation belongs to the category} \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]

Dummy Variables in Regression Models

Consider a regression model including a dummy variable: \[ y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \beta_2 D_i + \epsilon_i \]

\(x_i\): A continuous predictor.

\(D_i\): Dummy variable (e.g., political party affiliation, type of car).

Interpretation: \(\beta_2\) captures the difference in the response \(y\) when the category is present (i.e., \(D_i=1\)) versus absent.

The Dummy Variable Trap

Multicollinearity

- Multicollinearity happens in multivariate regression when two or more predictors are highly correlated, so they contain overlapping information.

- Perfect multicollinearity means one predictor is an exact linear combination of other predictors.

Problem: For a categorical variable with \(k\) levels, using all \(k\) dummies causes perfect multicollinearity:

- If you include all \(k\) dummy variables in the model, their values always sum to 1: \[ D_{1i} + D_{2i} + \cdots + D_{ki} = 1 \quad \text{(for each observation)} \]

This is problematic, because one dummy is completely predictable from the others.

The intercept already captures the constant part (1), making one of the dummy variables redundant.

Avoiding the Dummy Variable Trap

Solution: Drop one dummy (choose a reference category)

The reference category is represented by a combination of \(\texttt{borough}\) variables.

- Dummy for the reference category is 1 if all the rest of the dummies is 0.

- Dummy for the reference category is 0 otherwise.

Proper model: \[ y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 D_{1, i} + \beta_2 D_{2, i} + \cdots + \beta_{k-1} D_{(k-1), i} + \epsilon_i \]

Interpretation:

- Each \(\beta_j\) (for \(j=1,2,\ldots,k-1\)) represents the difference from the reference category.

Dummy Variable Regression in R

In R, factors automatically generate dummies and avoid the dummy variable trap.

# Set reference level (omit dummy for Manhattan)

dtrain <- dtrain |>

mutate(borough_name = factor(borough_name)) |>

mutate(borough_name = relevel(borough_name, ref = "Manhattan"))

dtest <- dtest |>

mutate(borough_name = factor(borough_name)) |>

mutate(borough_name = relevel(borough_name, ref = "Manhattan"))

m3 <- lm(sale_price ~ gross_square_feet + age + borough_name, data = dtrain)

stargazer(

m3,

type = "html",

title = "Multivariate Regression with Borough Dummies (Reference = Manhattan)",

dep.var.labels = "sale_price",

digits = 3

)Residual Plots

Residuals

- Model equation: \(Y_{i} \,=\, \beta_{0} \,+\, \beta_{1}X_{1,i} \,+\, \beta_{2}X_{2,i}\)

- \(\epsilon_i\) is a random noise, or a statistical error:

\[ \epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2) \]

Errors have a mean value of 0 with constant variance \(\sigma^2\).

Errors are uncorrelated with \(X_{1,i}\) and with \(X_{2, i}\).

Residuals

If we re-arrange the simple regression equation, \[\begin{align} {\epsilon}_{i} \,=\, Y_{i} \,-\, (\, {\beta}_{0} \,+\, {\beta}_{1}X_{1,i} \,). \end{align}\]

\(\texttt{residual_error}_{i}\) can be thought of as the expected value of \(\epsilon_{i}\), denoted by \(\hat{\epsilon_{i}}\).

\[ \begin{align} \hat{\epsilon_{i}} \,=\, &Y_i \,-\, \hat{Y}_i\\ \,=\, &Y_{i} \,-\, (\, \hat{\beta_{0}} \,+\, \hat{\beta_{1}}X_{1,i} \,) \end{align} \]

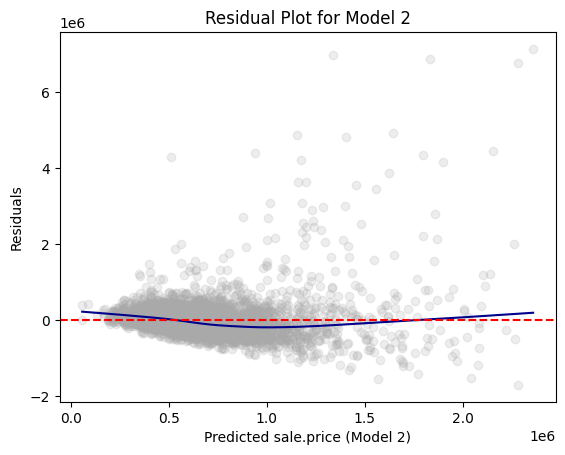

Residual Plots

Residual plot: scatterplot of

- fitted values on x-axis

- residuals on y-axis

- fitted values on x-axis

A residual plot can be used to diagnose the quality of model results.

We assume that \(\epsilon_{i}\) have a mean value of 0 with constant variance \(\sigma^2\):

- A well-behaved residual plot should bounce randomly and form a cloud roughly at the level of zero residual, the perfect prediction line.

Residual Plots

- On average, are the predictions correct?

- Are there systematic errors?

Examples

Unbiasedness and Homoskedasticity

Unbiased: mean residual is ~0 within thin vertical strips

Homoskedastic: similar spread of residuals across fitted values

If residual variance changes with fitted values ⇒ heteroscedasticity

What happens if biased?

- The model consistently overpredicts or underpredicts for certain values.

- Indicates that the model might be misspecified—perhaps missing important variables or using an incorrect functional form.

- Leads to biased parameter estimates, meaning the coefficients are systematically off, reducing the validity of predictions and inferences.

What happens if heteroscedasticity is present?

- Consequences of heteroscedasticity:

- 📉 Inefficient coefficient estimates: Estimates remain unbiased but are no longer efficient (i.e., they don’t have the smallest variance).

- ❌ Biased standard errors: Leads to unreliable p-values and confidence intervals, potentially resulting in invalid hypothesis tests.

- ⚠️ Misleading inferences: Predictors may appear statistically significant or insignificant incorrectly.

- 🎯 Poor predictive performance: The model might perform poorly on future data, especially if the residual variance grows with higher predicted values.

Residual Plot in R

aug_m2 <- augment(m2) # broom::augment()

ggplot(aug_m2, aes(x = .fitted, y = .resid)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.25) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE, method = "loess") +

labs(

x = "Fitted values (Model 2)",

y = "Residuals",

title = "Residual Plot for Model 2"

)Hypothesis Testing on Beta Coefficient

Hypothesis Testing on Beta Coefficient

To determine whether an independent variable has a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable in a linear regression model.

Consider the following linear regression model: \[ y_{i} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1,i} + \beta_2 x_{2,i} + \dots + \beta_k x_{k,i} + \epsilon_{i} \]

\(y\): Outcome

\(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_k\): Predictors

\(\beta_0\): Intercept

\(\beta_1, \beta_2, \dots, \beta_k\): Coefficients

\(\epsilon_{i}\): Error term

Hypotheses and Test Statistic

We test whether a specific coefficient \(\beta_j\) significantly differs from zero:

- Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): \(\beta_j = 0\) (No relationship)

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_A\)): \(\beta_j \neq 0\) (Significant relationship)

- Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): \(\beta_j = 0\) (No relationship)

The t-statistic is used to test each coefficient: \[ t = \frac{\hat{\beta_j} - 0}{SE(\hat{\beta_j})} \]

\(\hat{\beta_j}\): Estimated coefficient

\(SE(\hat{\beta_j})\): Standard error of the estimate

Hypothesis Testing - Decision Rule and Interpretation

- Calculate the p-value based on the t-distribution with \(n - k - 1\) degrees of freedom.

- Compare p-value with significance level \(\alpha\) (e.g., 0.05):

- If \(p \leq \alpha\): Reject \(H_0\) (Significant)

- If \(p > \alpha\): Fail to reject \(H_0\) (Not significant)

- In our course, stars in a regression table mean a significance level:

*(10%);**(5%);***(1%)

- Reject \(H_0\): There is sufficient evidence to suggest a statistically significant relationship between \(x_j\) and \(y\).

- Fail to reject \(H_0\): No statistically significant evidence of a relationship between \(x_j\) and \(y\).

Interpreting Beta Estimates

Interpreting Estimated Beta Coefficients

The model equation is \[\begin{align}

\texttt{sale_price[i]} \;=\;\, &\texttt{b0} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b1*gross_square_feet[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b2*age[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{b3*Bronx[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b4*Brooklyn[i]} \,+\,\\&\texttt{b5*Queens[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b6*Staten Island[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{e[i]}

\end{align}\] - The reference level of borough_name variables is Manhattan.

Interpreting Estimated Beta Coefficients

1. gross_square_feet

- Consider the predicted sales prices of the two houses,

AandB.- Both

AandBare inBronxand with the sameage. gross_square_feetof houseAis 2001, while that of houseBis 2000.

- Both

- All else being equal, an increase in

gross_square_feetby one unit is associated with an increase insale_priceby \(\hat{\beta_{1}}\).- Why?

Interpreting Estimated Beta Coefficients

1. gross_square_feet

\[ \begin{align}\widehat{\texttt{sale_price[A]}} \;=\quad& \hat{\texttt{b0}} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*gross_square_feet[A]} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b2}}\texttt{*age[A]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{*Bronx[A]}\,+\,\hat{\texttt{b4}}\texttt{*Brooklyn[A]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b5}}\texttt{*Queens[A]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b6}}\texttt{*Staten Island[A]}\\ \widehat{\texttt{sale_price[B]}} \;=\quad& \hat{\texttt{b0}} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*gross_square_feet[B]} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b2}}\texttt{*age[B]}\,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{*Bronx[B]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b4}}\texttt{*Brooklyn[B]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b5}}\texttt{*Queens[B]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b6}}\texttt{*Staten Island[B]} \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align}\Leftrightarrow\qquad&\widehat{\texttt{sale_price[A]}} \,-\, \widehat{\texttt{sale_price[B]}}\qquad \\ \;=\quad &\hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*}(\texttt{gross_square_feet[A]} - \texttt{gross_square_feet[B]})\\ \;=\quad &\hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*}\texttt{(2001 - 2000)} \,=\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\qquad\qquad\quad\;\; \end{align} \]

Interpreting Estimated Beta Coefficients

2. borough_nameBronx

Consider the predicted sales prices of the two houses,

AandC.- Both

AandCare with the sameageand the samegross_square_feet. Ais inBronx, andCis inManhattan.

- Both

All else being equal, an increase in

borough_nameBronxby one unit is associated with an increase insale_pricebyb3.Equivalently, all else being equal, being in

Bronxrelative to being a inManhattanis associated with a decrease insale_priceby|b3|.- Why?

Interpreting Estimated Beta Coefficients

2. borough_nameBronx

\[ \begin{align}\widehat{\texttt{sale_price[A]}} \;=\quad& \hat{\texttt{b0}} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*gross_square_feet[A]} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b2}}\texttt{*age[A]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{*Bronx[A]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b4}}\texttt{*Brooklyn[A]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b5}}\texttt{*Queens[A]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b6}}\texttt{*Staten Island[A]}\\ \widehat{\texttt{sale_price[C]}} \;=\quad& \hat{\texttt{b0}} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{*gross_square_feet[C]} \,+\, \hat{\texttt{b2}}\texttt{*age[C]}\,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{*Bronx[C]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b4}}\texttt{*Brooklyn[C]} \,+\,\\ &\hat{\texttt{b5}}\texttt{*Queens[C]}\,+\, \hat{\texttt{b6}}\texttt{*Staten Island[C]} \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align}\Leftrightarrow\qquad&\widehat{\texttt{sale_price[A]}} \,-\, \widehat{\texttt{sale_price[C]}}\qquad \\ \;=\quad &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{*}\texttt{Bronx[A]} \\ \;=\quad &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\;\;\;\,\end{align} \]

Coefficient Plot in R

coef_df <- tidy(m3, conf.int = TRUE)

ggplot(coef_df |> filter(term != "(Intercept)"),

aes(x = reorder(term, estimate), y = estimate, ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high)) +

geom_pointrange() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dashed") +

coord_flip() +

labs(

x = "Terms",

y = "Estimate (95% CI)",

title = "Coefficient Plot (Model with Borough Dummies)"

)Linear Regression with Log Transformation

Linear Regression with Log Transformation

The model equation with log-transformed \(\texttt{sale.price[i]}\) is \[\begin{align} \log(\texttt{sale.price[i]}) \;=\;\, &\texttt{b0} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b1*gross.square.feet[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b2*age[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{b3*Bronx[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b4*Brooklyn[i]} \,+\,\\&\texttt{b5*Queens[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b6*Staten Island[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{e[i]}. \end{align}\]

- Note that the reference level for

borough_nameisManhattan.

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

1. gross_square_feet

- Let’s re-consider the two properties \(\texttt{A}\) and \(\texttt{B}\).

- \(\texttt{gross.square.feet[A]} = 2001\) and \(\texttt{gross.square.feet[B]} = 2000\).

- Both are in the same borough.

- Both properties’ ages are the same.

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

1. gross_square_feet

- If we apply the rule above for \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[A]}\) and \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[B]}\),

\[\begin{align}&\log(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[A]}) - \log(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[B]}) \\ \,=\, &\hat{\texttt{b1}}\,*\,(\texttt{gross.square.feet[A]} \,-\, \texttt{gross.square.feet[B]})\\ \,=\, &\hat{\texttt{b1}}\end{align}\]

So we can have the following: \[ \begin{align} &\Leftrightarrow\qquad\frac{\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}}}{ \widehat{\texttt{sale.price[B]}}} \;=\; \texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{)}\\ \quad&\Leftrightarrow\qquad\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}} \;=\; \widehat{\texttt{sale.price[B]}} * \texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{)} \end{align} \]

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

1. gross_square_feet

- Suppose \(\texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b1}}\texttt{)} = 1.000431\).

- Then \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}}\) is \(1.000431\times\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[B]}}\).

- All else being equal, an increase in \(\texttt{gross.square.feet}\) by one unit is associated with an increase in \(\texttt{sale.price}\) by 0.0431%.

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

2. borough_nameBronx

- Let’s re-consider the two properties \(\texttt{A}\) and \(\texttt{C}\).

Ais inBronx, andCis inManhattan.- Both

AandC’sageare the same. - Both

AandC’sgross.square.feetare the same.

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

2. borough_nameBronx

- If we apply the

log()-exp()rules for \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[A]}\) and \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[C]}\),

\[\begin{align}&\log(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[A]}) - \log(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price}}\texttt{[C]}) \\ \,=\, &\hat{\texttt{b3}}\,*\,(\texttt{borough_Bronx[A]} \,-\, \texttt{borough_Bronx[C]})\,=\, \hat{\texttt{b3}}\end{align}\]

So we can have the following: \[ \begin{align}&\Leftrightarrow\qquad\frac{\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}}}{ \widehat{\texttt{sale.price[C]}}} \;=\; \texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{)}\\ \quad&\Leftrightarrow\qquad\,\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}} \;=\; \widehat{\texttt{sale.price[C]}} * \texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{)} \end{align} \]

Beta Estimates for Log-transformed Variables

2. borough_nameBronx

- Suppose \(\texttt{exp(}\hat{\texttt{b3}}\texttt{)} = 0.2831691\).

- Then \(\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[A]}}\) is \(0.2831691\times\widehat{\texttt{sale.price[B]}}\).

- All else being equal, an increase in \(\texttt{borough_Bronx}\) by one unit is associated with a decrease in \(\texttt{sale.price}\) by (1 - 0.2831691) = 71.78%.

- All else being equal, being in

Bronxrelative to being inManhattanis associated with a decrease in \(\texttt{sale.price}\) by 71.78%.

Linear Regression with Interaction Terms

Linear Regression with Interaction Terms

Motivation

Does the relationship between

sale.priceandgross.square.feetvary byborough_name?- How can linear regression address the question above?

Linear Regression with Interaction Terms

The linear regression with an interaction between predictors \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) are: \[Y_{\texttt{i}} \,=\, b_{0} \,+\, b_{1}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{2}\,X_{2,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{3}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}}\times \color{Red}{X_{2,\texttt{i}}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\;.\]

where

- \(i\;\): \(\;\;i\)-th observation in the training DataFrame, \(i = 1, 2, 3, \cdots\).

- \(Y_{i}\,\): \(\;i\)-th observation of outcome \(Y\).

- \(X_{p, i}\,\): \(i\)-th observation of the \(p\)-th predictor \(X_{p}\).

- \(e_{i}\;\): \(\;i\)-th observation of statistical error.

Linear Regression with Interaction Terms

- The linear regression with an interaction between predictors \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) are: \[Y_{\texttt{i}} \,=\, b_{0} \,+\, b_{1}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{2}\,X_{2,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{3}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}}\times \color{Red}{X_{2,\texttt{i}}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\;.\]

Interaction

- The relationship between \(X_{1}\) and \(Y\) varies by values of \(b_{3}\, X_{2}\): \[\frac{\Delta Y}{\Delta X_{1}} \,=\, b_{1} + b_{3}\, X_{2}\]

Example

- \(X_{2}\) is often a dummy variable. If \(b_{3} \neq 0\) and \(X_{2, \texttt{i}} = 1\), \[\frac{\Delta Y}{\Delta X_{1}} \,=\, b_{1} + b_{3}\]

Interaction with a Dummy Variable

The linear regression with an interaction between predictors \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\in\{\,0, 1\,\}\) are: \[Y_{\texttt{i}} \,=\, b_{0} \,+\, b_{1}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{2}\,X_{2,\texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{3}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}}\times \color{Red}{X_{2,\texttt{i}}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}},\] where \(X_{\,2, \texttt{i}}\) is either 0 or 1.

For \(\texttt{i}\) such that \(X_{\,2, \texttt{i}} = 0\), the model is \[Y_{\texttt{i}} \,=\, b_{0} \,+\, b_{1}\,X_{1,\texttt{i}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\;\;\]

For \(\texttt{i}\) such that \(X_{\,2, \texttt{i}} = 1\), the model is \[Y_{\texttt{i}} \,=\, (\,b_{0} \,+\, b_{2}\,) \,+\, (\,b_{1}\,+\, b_{3}\,)\,X_{1,\texttt{i}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\qquad\qquad\]

Example 1

- Is

sale.pricerelated withgross.square.feet? \[ \begin{align} \texttt{sale_price[i]} \;=\;\, &\texttt{b0} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b1*Bronx[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b2*Brooklyn[i]} \,+\,\\&\texttt{b3*Queens[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b4*Staten Island[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{b5*age[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{b6*gross_square_feet[i]} \,+\,\texttt{e[i]} \end{align} \]

Example 2

- Does the relationship between

sale.priceandgross.square.feetvary byborough_name? \[ \begin{align} \texttt{sale_price[i]} \;=\;\, &\texttt{b0} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b1*Bronx[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b2*Brooklyn[i]} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b3*Queens[i]} \,+\,\texttt{b4*Staten Island[i]}\,+\, \\ &\texttt{b5*age[i]}\,+\,\\ &\texttt{b6*gross_square_feet[i]} \,+\,\\ &\texttt{b7*gross_square_feet[i]*Bronx[i]} \,+\, \\ &\texttt{b8*gross_square_feet[i]*Brooklyn[i]} \,+\, \\ &\texttt{b9*gross_square_feet[i]*Queens[i]} \,+\, \\ &\texttt{b10*gross_square_feet[i]*Staten Island[i]} \,+\, \texttt{e[i]} \\ \end{align} \]

Log-Log Linear Regression

Log-Log Linear Regression

- To estimate the price elasticity of orange juice (OJ), we will use sales data for OJ from Dominick’s grocery stores in the 1990s.

- Weekly

priceandsales(in number of cartons “sold”) for three OJ brandsTropicana, Minute Maid, Dominick’s - A dummy,

ad, showing whether eachbrandwas advertised (in store or flyer) that week.

- Weekly

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

sales |

Quantity of OJ cartons sold |

price |

Price of OJ |

brand |

Brand of OJ |

ad |

Advertisement status |

Estimating Price Elasticity

- The following model estimates the price elasticity of demand for a carton of OJ: \[\begin{align} \log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) &\,=\, \;\; b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}\\ &\quad\,+\, b_{\texttt{price}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}},\\ \text{where}\qquad\qquad&\\ \texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}} &\,=\, \begin{cases} \texttt{1} & \text{ if an orange juice } \texttt{i} \text{ is } \texttt{Tropicana};\\\\ \texttt{0} & \text{otherwise}.\qquad\qquad\quad\, \end{cases}\\ \texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}} &\,=\, \begin{cases} \texttt{1} & \text{ if an orange juice } \texttt{i} \text{ is } \texttt{Minute Maid};\\\\ \texttt{0} & \text{otherwise}.\qquad\qquad\quad\, \end{cases} \end{align}\]

Estimating Price Elasticity

The following model estimates the price elasticity of demand for a carton of OJ: \[\log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\, \quad\;\; b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}\\ \,+\, b_{\texttt{price}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\]

When \(\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}\,=\,0\) and \(\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}\,=\,0\), the beta coefficient for the intercept \(b_{\texttt{intercept}}\) gives the value of Dominick’s log sales at \(\log(\,\texttt{price[i]}\,) = 0\).

The beta coefficient \(b_{\texttt{price}}\) is the price elasticity of demand.

- It measures how sensitive the quantity demanded is to its price.

Estimating Price Elasticity

For small changes in variable \(x\) from \(x_{0}\) to \(x_{1}\), the following equation holds: \[\Delta \log(x) \,= \, \log(x_{1}) \,-\, \log(x_{0}) \approx\, \frac{x_{1} \,-\, x_{0}}{x_{0}} \,=\, \frac{\Delta\, x}{x_{0}}.\]

The coefficient on \(\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\), \(b_{\texttt{price}}\), is therefore \[b_{\texttt{price}} \,=\, \frac{\Delta \log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}})}{\Delta \log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})}\,=\, \frac{\frac{\Delta \texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}}{\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}}}{\frac{\Delta \texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}}{\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}}}.\]

All else being equal, an increase in \(\texttt{price}\) by 1% is associated with a decrease in \(\texttt{sales}\) by \(b_{\texttt{price}}\)%.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) 1

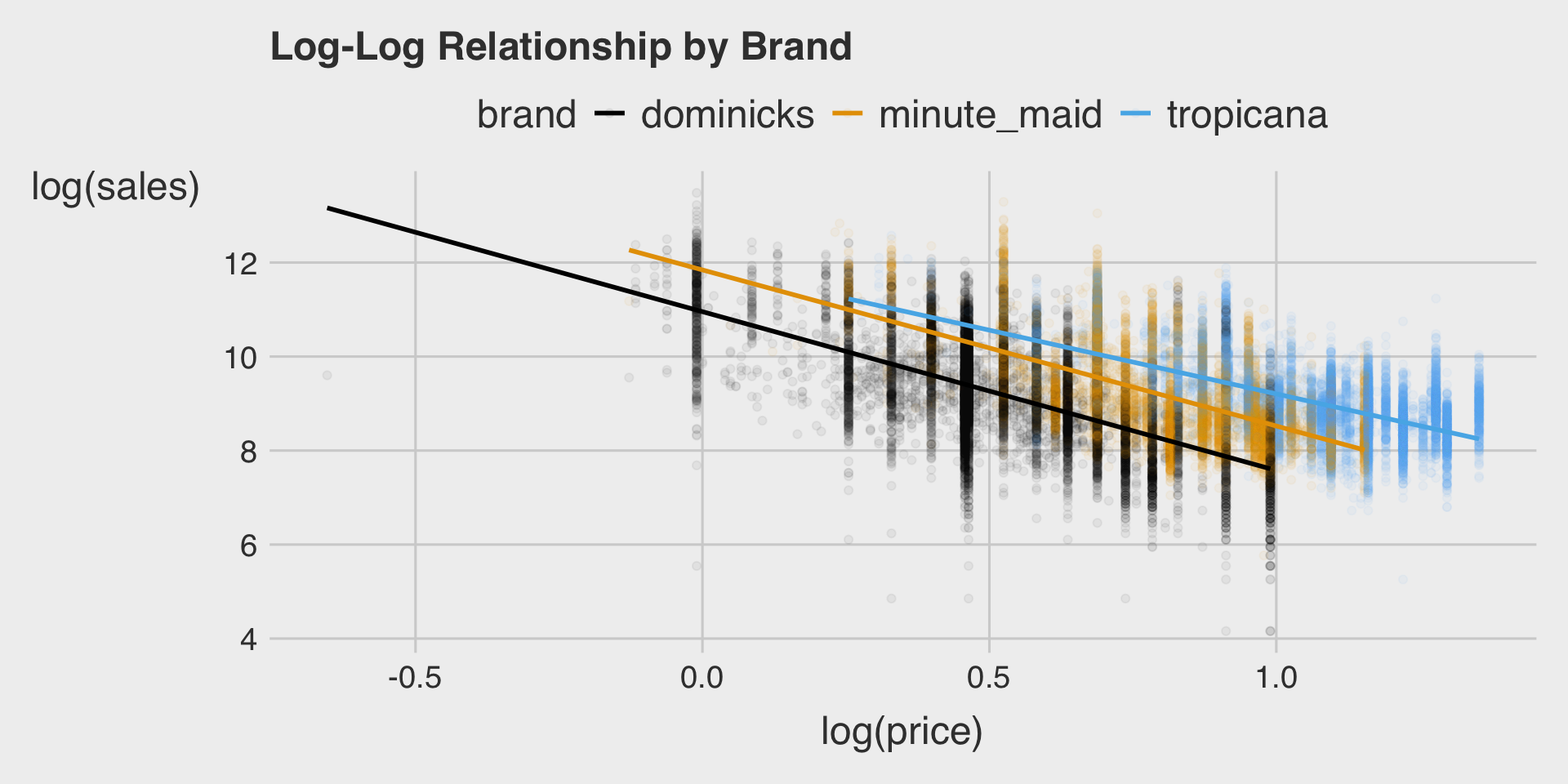

Describe the relationship between log(price) and log(sales) by brand.

EDA 2

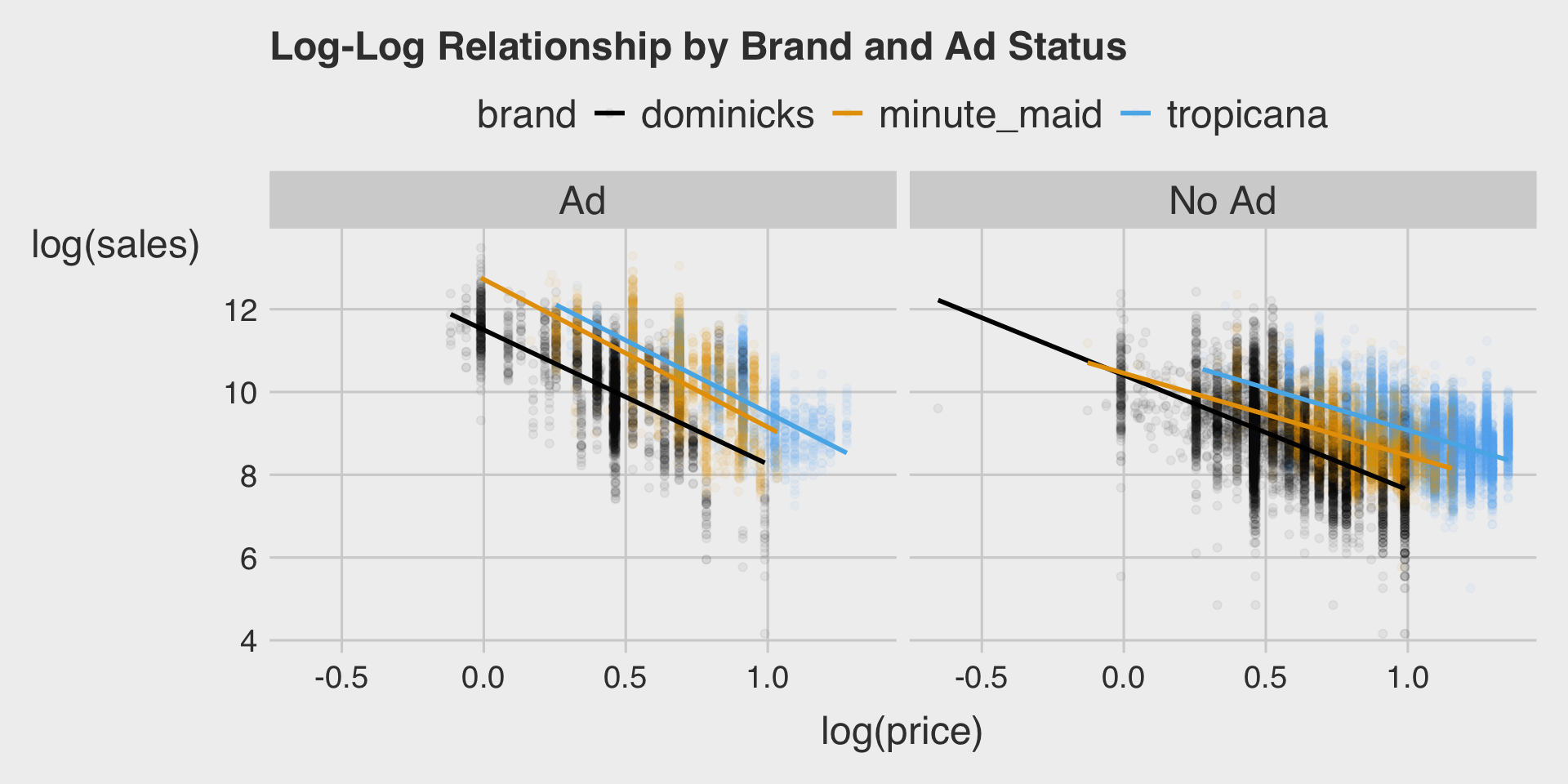

Describe the relationship between log(price) and log(sales) by brand and ad.

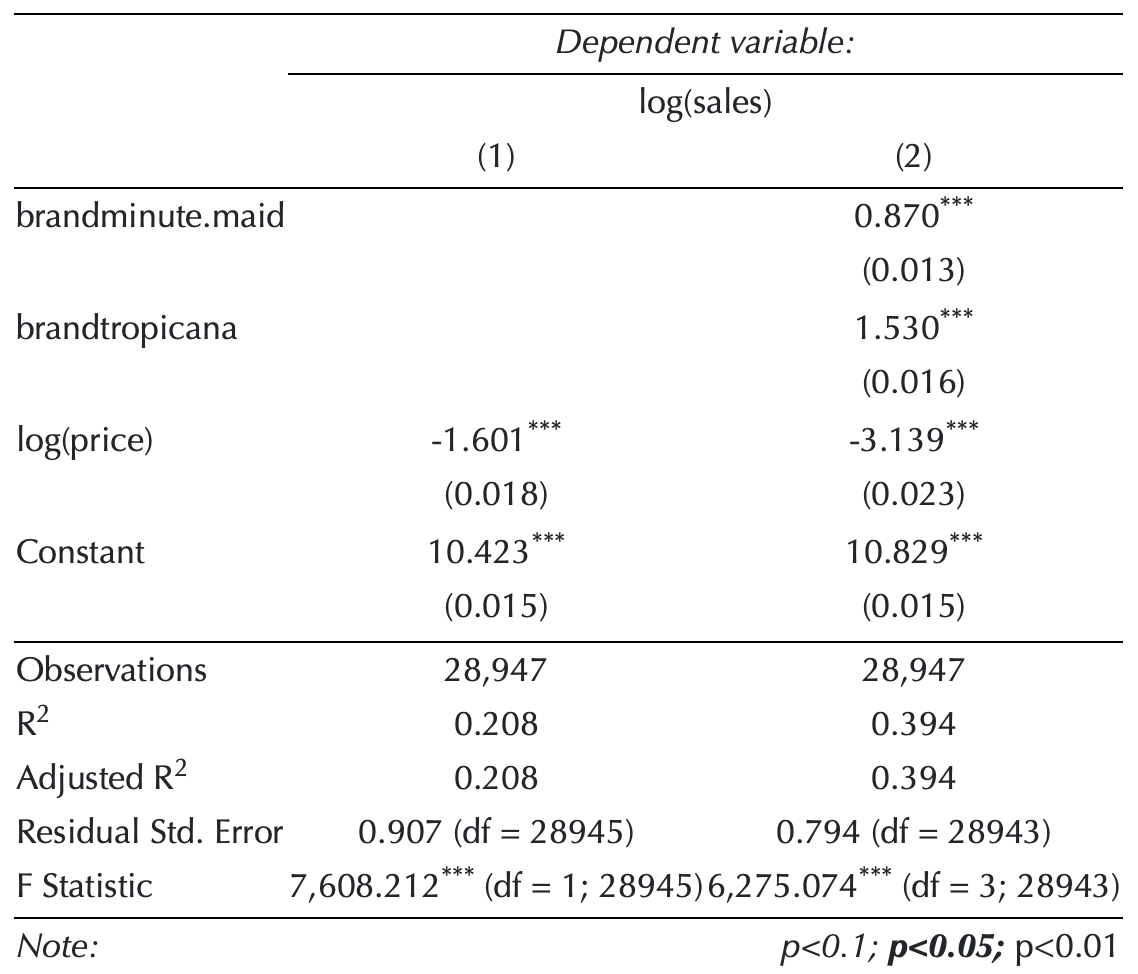

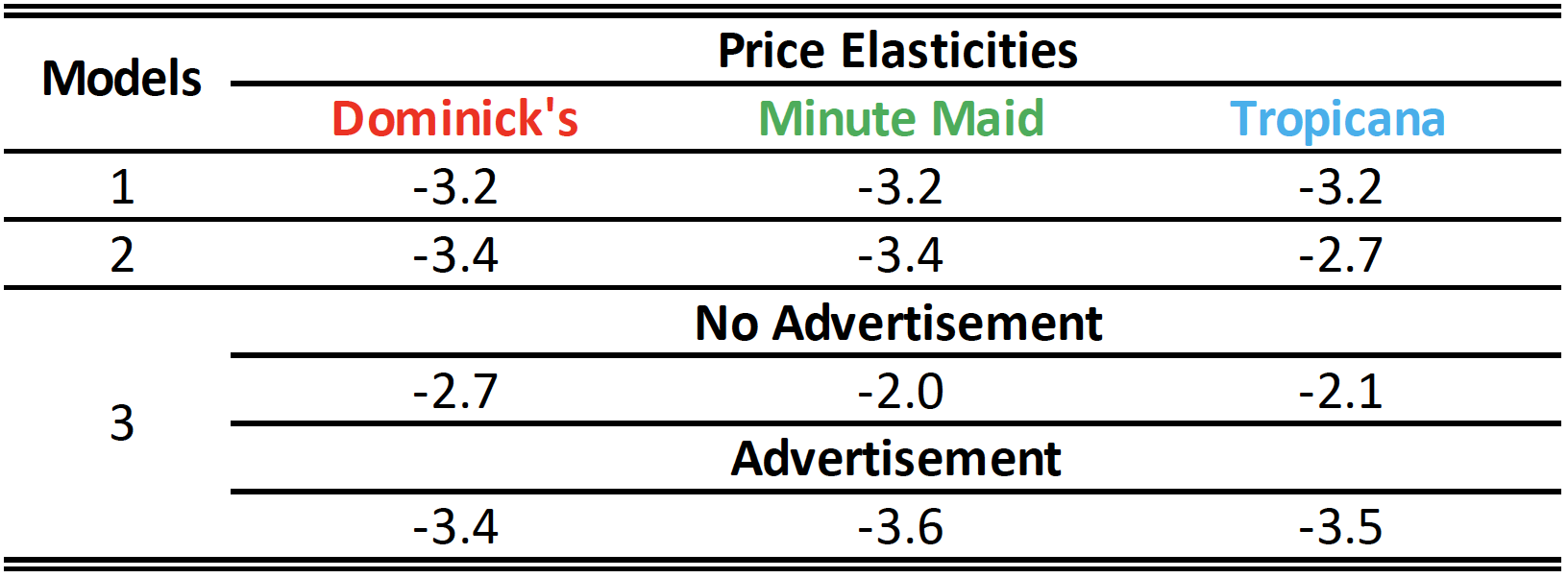

Model 1: Brand + log(price)

- Let’s train the first model,

model_1: \[ \begin{align} \log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\, &\quad\;\; b_{\texttt{intercept}} \\ &\,+\,b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}\\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}} \end{align} \]

Model 2: Brand-Specific Elasticity (Interaction)

How does the relationship between

log(sales)andlog(price)vary bybrand?- Let’s train the second model,

model_2, that addresses the above question: \[ \begin{align} \log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\,&\;\; \quad b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, \color{Green}{b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} \,+\, \color{Blue}{b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}}\\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \\ &\, +\, b_{\texttt{price*mm}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\,\times\,\color{Green} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price*tr}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\,\times\,\color{Blue} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}} \end{align} \]

- Let’s train the second model,

Model 2: Brand-Specific Elasticity (Interaction)

For \(\texttt{i}\) such that \(\color{Green}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} = 0\) and \(\color{Blue}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}} = 0\), the model equation is: \[\log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\, \; \,b_{\texttt{intercept}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\\ \qquad\,+\, b_{\texttt{price}} \,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\,.\qquad\qquad\;\]

For \(\texttt{i}\) such that \(\color{Green}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} = 1\) and \(\color{Blue}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}} = 0\), the model equation is: \[\log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\, \; (\,b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,)\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\\ \qquad\!\,+\,(\, b_{\texttt{price}} \,+\, \color{Green}{b_{\texttt{price*mm}}}\,)\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\,.\]

For \(\texttt{i}\) such that \(\color{Green}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} = 0\) and \(\color{Blue}{\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}} = 1\), the model equation is: \[\log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\, \; (\,b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,)\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\\ \qquad\!\,+\,(\, b_{\texttt{price}} \,+\, \color{Blue}{b_{\texttt{price*tr}}}\,)\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}}\,.\]

Model 3: Brand × Price × Ad (Full Interaction)

- Would advertisement affect not only sales but also price sensitivity in a brand-specific way?

- Let’s train the third model,

model_3: \[ \begin{align} \log(\texttt{sales}_{\texttt{i}}) \,=\,\quad\;\;& b_{\texttt{intercept}} \,+\, \color{Green}{b_{\,\texttt{mm}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}} \,+\, \color{Blue}{b_{\,\texttt{tr}}\,\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}} \\ &\,+\; b_{\,\texttt{ad}}\,\color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}} \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{mm*ad}}\,\color{Green} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}}\,\times\, \color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}}\,+\, b_{\texttt{tr*ad}}\,\color{Blue} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}}\,\times\, \color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}} \\ &\,+\; b_{\texttt{price}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \qquad\qquad\qquad\;\;\;\;\, \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price*mm}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\,\times\,\color{Green} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\;\, \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price*tr}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\,\times\,\color{Blue} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\;\, \\ & \,+\, b_{\texttt{price*ad}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}})\,\times\,\color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}}\qquad\qquad\qquad\;\;\, \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price*mm*ad}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,\times\,\,\color{Green} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{mm}, \texttt{i}}}\,\times\, \color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}} \\ &\,+\, b_{\texttt{price*tr*ad}}\,\log(\texttt{price}_{\texttt{i}}) \,\times\,\,\color{Blue} {\texttt{brand}_{\,\texttt{tr}, \texttt{i}}}\,\times\, \color{Orange}{\texttt{ad}_{\,\texttt{i}}} \,+\, e_{\texttt{i}} \end{align} \]

- Let’s train the third model,

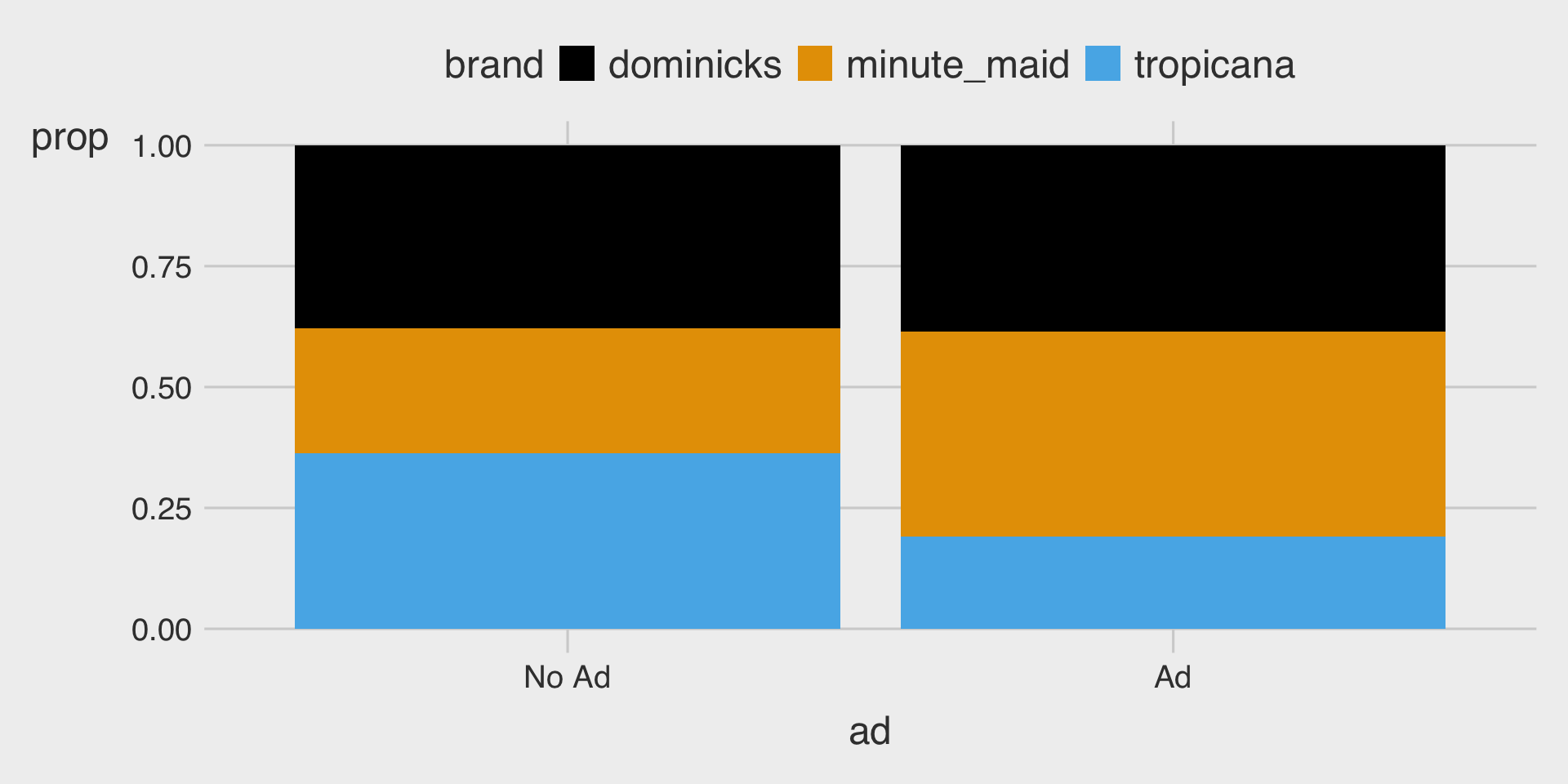

EDA 3

Describe how the distribution of brand varies by ad using stacked bar charts.

- Model 3 assumes that the relationship between

priceandsalescan vary byad.

R Code for Model 1: Brand + log(price)

R Code for Model 2: Brand-Specific Elasticity (Interaction)

R Code for Model 3: Brand × Price × Ad (Full Interaction)

Results

How would you explain different estimation results across different models?

Which model do you prefer? Why?